Sarah Fay on curing without fixing

A subversive redefinition of healing from someone who’s lived inside the psychiatry's alphabet soup

If being cured just means I’m taking care of myself really well, then I’m good. That’s all I need.

-Sarah Fay, author, journalist, professor, activist

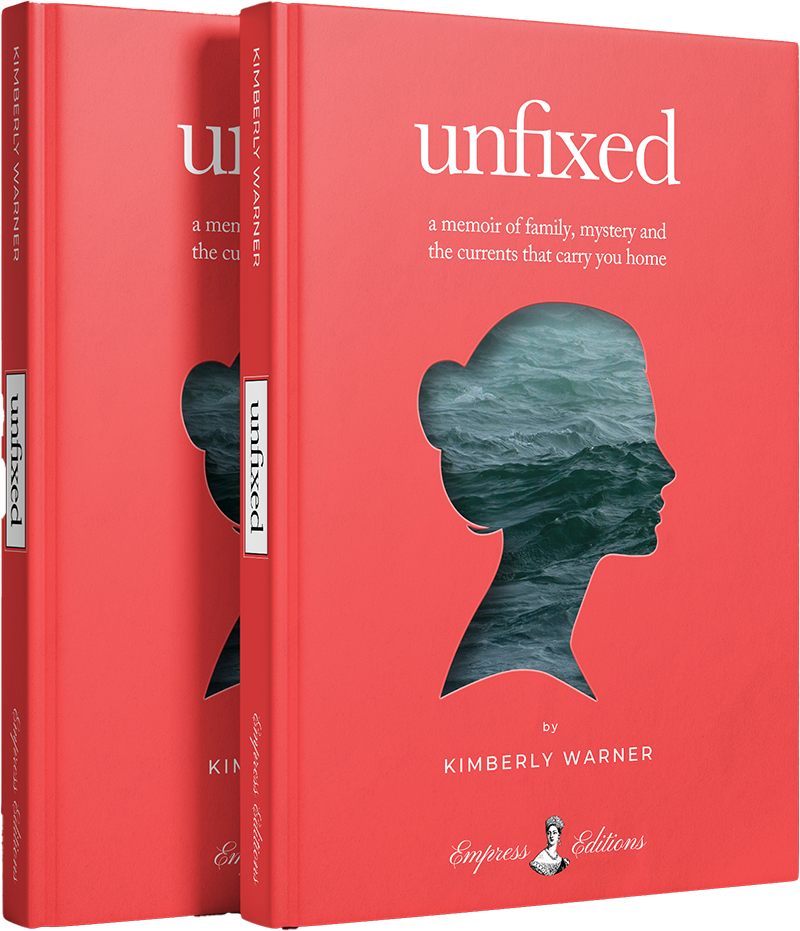

Before I ever read Pathological: The True Story of Six Misdiagnoses I found Sarah Fay through her serialized memoir Cured on Substack. I was immediately struck by her voice—clear, exacting, and unflinchingly generous. The title itself caught my attention too. Cured felt like a provocative mirror to my own work with Unfixed. Together, those two words seemed to hold the tension so many of us live inside: the longing for resolution, and the truth of life as an ongoing unfolding.

Not long after, I discovered Pathological which was first published during the pandemic and recently re-released into a culture more ready to receive it. And personally, Sarah was one of the first people who helped me find my footing when I began sharing Unfixed publicly on Substack, and I am forever grateful.

This conversation took off with that rare, infectious energy, the kind that builds slowly, then catches fire midway through and carries you with it. Sarah and I met in the layered terrain of diagnosis, uncertainty, and what it means to heal. But it never felt heavy. Instead, it felt alive, like we were tossing matchsticks and watching ideas flare.

We talked about the strange relief and quiet harm of being named, especially too young, especially as a girl. About how diagnosis can obscure emotional truth even as it pretends to explain it. Sarah spoke to the gender bias still embedded in psychiatry, the culture’s growing hunger for certainty, and the danger of folding ourselves too tightly around a label.

Then came the turning point: the moment a psychiatrist finally said to her, “I don’t know what you have.” It was shattering and oddly freeing. From there, the conversation sparked into how healing might be less about eliminating symptoms and more about learning to care. How a full life can make room for grief, joy, anxiety, panic, and presence.

If you’ve ever felt stuck between labels, or unsure what it means to be “well,” I think you’ll find solace and insight in Sarah’s refreshing wisdom and honesty. She doesn’t offer easy answers, but she offers something better: a hard-earned demonstration of how to live with the questions.

TRANSCRIPT:

Kimberly

Okay, my gosh, Sarah, it's been too long, first of all. It's been too long since we've had a face-to-face. Of course, we've interacted and all of those lovely things on Substack, but it's just wonderful to see your face. And especially after reading your newly relaunched book, Pathological, we're gonna talk all about that. So if you don't already know, Sarah's an award-winning author, New York Times contributor, creative writing professor at Northwestern, certified peer recovery support specialist, and incredible advocate for the mental health community, powerful speaker, and really ultimately reframing how we talk and think about mental illness. And so her book, Pathological: The True Story of Six Misdiagnoses was just announced on US Today's bestseller list and Apple Books Pick of the Month, which I just also saw. So this is making waves in the world right now. This is very exciting that we get to talk today. But this book is part memoir, but also a deep dive into mental health and like an investigatory. Is that a word? Investigatory—

Sarah

It is now!

Kimberly

—it is now…into the mental health system. And it's one of those books that manages to be both rigorously researched and deeply personal. So Sarah, what struck me most while reading Pathological was not just the clarity with which you write, but the absolute generosity beneath it. You don't question the system, you question the questions, which I love.

And so much of your work feels like an offering of not answers, but an orientation for those of us that are navigating the mental health world or also in the caregiving realm. So I am incredibly grateful to have you here today. I'm gonna do a little—Look! Pathological right here on my desk! So we're gonna talk a lot about this today.

I wanna open with how Pathological was not just about a diagnosis, but a question about who gets to name your experience and what happens when those names feel like they have bound you into something that you don't want. You wrote, “I was so attached to my diagnosis that I couldn't see myself without it.”

Can you take me back to the first time you felt uneasy about the labels that were offered to you?

Sarah

I wish I'd felt more uneasy, but part of it is—and this, if there are any parents listening, anyone who has a child right now or teen or tween who's on social media will relate to this. So I was 12 when I received my first diagnosis. That's very young. And it was the 19, what was it? So it was 1980s. So it was not in the cultural conversation as much as it is now.

And I had been on a field trip, an eighth grade field trip, and I wasn't eating and basically couldn't keep down food, couldn't hold down water, got home. My parents rushed me to the emergency room as they should have. We ended up seeing my doctor and he looked at me, weighed me, heard what was happening according to my mother and said, “You're anorexic.”

So it wasn't, you have anorexia, it was an identity. It was something I was. I'd never heard the word. I had no idea what anorexia was, even though this was the memoir boom, but I was just too young. The eating disorder memoir boom. I say this to parents because right now on social media, we have people, young people self-diagnosing, diagnosing each other, diagnosing themselves, really almost relishing in diagnoses.

And that's fascinating to me. I'm not saying whether it's good or bad. It's just interesting to watch. And I think part of it is, it became this very easy answer to me about, Okay, I don't feel good. It means it's because of this diagnosis, not because my parents were divorcing. I was going to a new high school. I was incredibly sad and incredibly scared. And the way that manifests in my body is a stomach ache. I couldn't eat. I didn't want to eat, but not because I had necessarily a bad self-image or body image problem. That had never been discussed. It was just assumed by my behavior and what was happening. And again, he was my GP. He was just my general practitioner. Those are the people who are doing the lion's share of the diagnosing. So that was the first time I heard it, heard a word or heard a diagnosis.

And then flash forward in my 20s, I was diagnosed with anxiety, also with major depressive disorder. Then in my 30s, I was diagnosed with ADHD and obsessive compulsive disorder. Then I was diagnosed with ADHD and OCD with depressive and anxious elements, which was my favorite. It was like the salad. And then finally bipolar disorder and then bipolar II and then bipolar I. It was just this progression. And really, it shows a lot of things. The questions we can ask is, was I changing? Did I exhibit these different things as I went? Or were people just trying to name my mental and emotional pain? By giving it different names with these diagnoses, which then meant different treatments and different medications, of course or psychiatric drugs.

And that's the situation we find ourselves in right now, which is that DSM diagnoses, so the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, it is the way that we categorize our mental and emotional pain. And that's somewhat problematic or incredibly problematic, depending on the day or the situation you're in. But to your question, I really didn't question any of it.

Kimberly

All of those diagnoses.

Sarah

Never. I just assumed, we're getting to the bottom of something. And I know so many people, and I've heard from so many people who've had the same experience once Pathological came out, just readers getting in touch with me. And it's not necessarily, you again, I'm not against the DSM, although I think it's incredibly problematic and I would even say dangerous. But I don't have anything to replace that diagnostic system with. So unless I do, I'm not saying let's throw it out and a lot of people are. And I think psychiatrists should say that, people who are qualified to talk about that. I'm just saying that what I want to see is patients being more empowered by the truth about these diagnoses, which is that they are scientifically invalid and largely unreliable. And we can dive into what that means.

Kimberly

Wow.

And you talk about this emotional truth and how these diagnosis helped you explain that emotional truth. When you were being given these diagnoses, was there also a space for you to investigate those emotional truths or did it feel like a bandaid?

Sarah

It was, it's interesting because people do ask that. And I talk about it a lot in the book, um, which is I tried everything. I mean, I tried to yoga it down. I tried to meditate it down. I tried to run it down. I mean, I did all of that. I tried diet, like every diet in existence I have tried. And I did therapy. I did CBT. I did DBT. I did ACT. I've done them all. And you know, again, that's you know, not faulting those things and they're incredibly important. They just didn't work for me and I know they can work for some people.

Oddly, what did work was finding out the truth about diagnoses, which is that they're incredibly flawed, that I am not my diagnosis, that this is not actually anything to take too seriously. Now, if it gives you solace to have a diagnosis, if it makes you feel more empowered, by all means, you know, I'm absolutely in support of that. For me, it did not. It absolutely made me see myself as something to fix. It made me see myself as broken. It made me see myself as less than. And even if I felt somehow, I don’t want to say empowered, but special because I had it, which can be very comforting. It didn't ultimately lead me to live a full life. Quite the opposite. By the time I was in my 40s, I could no longer live independently. I was chronically suicidal. I was told that I would not live into old age. I would never have a long-term relationship. I would never hold a full-time job. These were the stereotypes around the diagnoses I was being given at that time, which was eventually bipolar I, which next to schizophrenia is about as serious, let's say, I shouldn't say that. All of them are serious, but in the eyes of the mental health community and certainly emergency rooms, that's how they're seen.

Kimberly

So there were so many different ways that you were trying to interpret these diagnoses and other people were interpreting them. And also you mentioned gender was a part of that as well. So can you tell me a little bit more? Let's go a little layer deeper. How did even being a woman affect your relationship to what you were experiencing and also your self-perception in these psychiatric spaces?

Sarah

It's such a good point to investigate, which is that if I had gone into the emergency room with my mother, with my parents, and I'm 12 years old and I'm a boy, and I'm not eating, and I'm not holding down food, I'm not holding down liquid, what do we think would have happened? My doctor weighs me as a boy, unlikely he would have said, You're anorexic. Very likely he would have sent me for tests. Now those tests wouldn't have delivered anything. So I'm not saying necessarily that that was the answer. But, of course we, you know, who knows, maybe he wouldn't have, but at that time boys were not thought to even have anorexia. They were not thought of as ever being able to get that diagnosis at the time. And that's only, it was maybe 10 years later that that started to be happening. And it's obviously it's not that boys don't get that.

Kimberly

Well, I will say—I'll interject just for a second. Just two weeks ago, a friend's son came back from college, had lost 25 pounds, was not eating anything, went to his GP and they ran a bunch of tests and they said, Oh, you broke up with your girlfriend. You're feeling sad. And that was where it ended up. And like you said, if it had been a girl, it might've been a different story.

Sarah

And that's so beautiful because “you're feeling sad.” No one said that to me. Your parents are divorcing. And I saw a psych, my parents sent me to a psychologist. So it wasn't as if I didn't see someone. He probably wasn't a great psychologist, obviously, or he just didn't, it wasn't a good fit, which happens all the time. But that didn't, I don't remember anyone ever saying that to me.

And I love that because he was also treated in a dignified way, which is, let's check and make sure nothing physically is wrong. We're not gonna dismiss you in some ways and just give you a label. The other thing is, what's the answer to all of this? People often ask me that when they read Pathological and they see that I'm really going through and as you said, doing a deep dive and investigating these diagnoses that we receive.

And for me, it's very close to what you're describing, which is you would go into a psychiatrist's office. He would do the usual, you know, you have a 30 minute session, and at the end he declares what you are, declares what you have. But instead of doing that, they would say something along the lines of—I can tell that you're incredibly sad, whatever it is, anxious, you're having hallucinations, you're doing these things. We don't know a lot about the brain, which is true, we do the best we can. And the way we do that are through these diagnoses. These diagnoses are not scientifically valid and they're not necessarily reliable. But this is the one I'm gonna use for this reason. And this is the medication that I recommend for this reason. What do you think about that?

Now I know some people, and certainly I was not in a position many times when I was chronically suicidal to have that conversation.

But even not to be asked, but just to be presented with the truth. I would have been far more empowered.

Kimberly

Yeah, absolutely. Do you think that that's happening more? I mean, are you having conversations, especially people that are reading your book and are coming to you? They're experiencing that from psychiatrists now, this empowering self-agency?

Sarah

Well, it's funny, my psychiatrist has said every medical resident should read your book.

Kimberly

Yes, they should.

Sarah

Because it's not being taught in medical schools. What we're talking about is not even being taught. The elephant in the room isn't even an elephant because they don't see a problem. They aren't even being taught that there's a problem. That's the first issue. And then what's interesting is when Pathological first came out, which was in 2022, it was the height of the pandemic. And everyone, perhaps rightfully so, the media, et cetera, was telling people get a diagnosis, get your child a diagnosis, get your dog a diagnosis. Everyone needs to be in therapy. And we were in a global crisis. It makes sense. But really the issue wasn't diagnosis. It shouldn't have been go get a diagnosis. It's get support. This is going to be heavy. But the people who experienced suddenly anxiety in the pandemic or depression, that's a very normal and like understandable response to a global pandemic. It is absolutely exactly how we should have been feeling. But when that happened, we were really ready for psychiatry to push back. We were just ready for, you know, to have this kind of controversy and them to really be negative and articles coming out about me. It was completely the opposite. Every single psychiatrist I heard from, mental health professional—and really there are so few right now who don't feel this—which is, know. We know it's a flawed system and we're doing our best, which I truly believe they are. Now there are a few outliers, I won't name names, but they are insistent about how great the DSM is, but that's something else. And then now though, but so who we heard from, the pushback we got was from the public.

I mean, my two publicists on Pathological both said to me they didn't believe my book because they said that their depression diagnoses really meant a lot to them and they didn't think it was harming them. So we got a lot, I mean, I don't wanna say a lot of pushback because we didn't, but now that I've relaunched it, and I think this is just to say things have changed and that's why I relaunched it. So we're three years later.

You've got kids diagnosing themselves on TikTok. You have all these people who receive diagnoses in the pandemic, suddenly, you know, wait, how long am I going to be on this medication for? Am I feeling better? You know, all of those questions are being asked or the diagnosis isn't helping. We're not necessarily, it's not working. It's not solving all of our problems. And so now that we put it out, so before there was this resistance to it and now it's just constant.

This is exactly what I'm going through. This is exactly what I'm experiencing. This is exactly what I did experience. It is this diagnosis after diagnosis after diagnosis, and no one telling you these are just names. These are just terms. These are just categories. This is just us doing the best we can. So it's been really fascinating to relaunch it and see how different things are.

Kimberly

Yeah. I can't wait to talk to you about that. Because even just the relaunching itself, I imagine, had brought up all kinds of things for you. I want to touch on something because I'm imagining going through all of this and then in hindsight, looking back with all the knowledge that you have now, I would feel anger. I would be really pissed. So how did you end up walking that tightrope of not getting into this anti-psychiatry versus pro-psychiatry thing because you do that beautifully and I could see how easy it would be to get on one side or the other.

Sarah

There were two parts to it. One, I was very angry. Don't get me wrong. Writing Pathological really helped. So first, mean, and I should say the New York Times in their review, which was very glowing, calls it “a fiery manifesto of a memoir.” The anger's in there. I don't think it's not fully a manifesto, but, most people don't see it that way. But so writing Pathological, that's my way of dealing with things. Even when I was very ill, I got an MFA and a master's and a PhD and people say you were so high functioning, but that was my escapism. That was just my way. Research just is something I do and I always have. So that was just a way of dealing with it. Some find their way to perhaps alcohol or drugs or food or whatever it might be. And mine was just, is an addiction to really researching things and trying to figure them out.

And so writing Pathological and finding out about the DSM, that was one part of it that made me oddly less angry, though I was still quite angry up until a couple of years ago, so about a year after Pathological came out. The other part of it though, why I wasn't as angry as maybe I could have been, is that my psychiatrist, so the final psychiatrist I saw, is the reason I've healed. He's the reason I wrote Pathological, which is that I had been seeing a psychiatrist who was also my therapist. So he was playing both roles, ill-advised, everyone listening, ill-advised, because you don't have anyone to talk to about your psychiatrist and no one to talk to about your therapist. So you get locked into them, which is what happened. He was a bipolar expert. He really wanted me to be bipolar. And I was starting to question it.

Are you sure that this is what I am? Are you sure? And again, even this terminology, the way I'm saying it is ridiculous. It's not what I am. I don't say I'm a cold, I'm a flu. It's not how we look at diagnoses. That's not how we should be talking about them, but it is. So he and I had kind of, we're breaking up, let's say, and he would not refill my medications because he did not want me to stop seeing him.

And I was, suicidal, my sister swept in and found me a psychiatrist and I went to see him and I was sitting across from him. We had the 30 minute intake and at the end I waited for him to either reify the bipolar diagnosis or give me a new diagnosis and he looked at me and he said, “I don't know what you have.” And it just like blew me open. I mean, and I describe it in the book that the world looked different. It was completely different. was just like the sky looked crisper. It was a terrible, terrible cold day in Chicago and everything, the sidewalk looked harsher in some ways. So it wasn't like the sky opened up and was beautiful. It was harder. It was harsher not to know what was causing, supposedly, the pain and anguish that I was going through.

But I continued to see him and he really opened up for me—and I still don't know what he's written on my chart to this day. And I still see him every year because I see a GP. Why wouldn't I? And this gets into the more, you know, the complications that I know so many people in your community have experienced, which is that these medications that they give us, your body becomes dependent on them, not in an addiction way, but in a dependence way. And they can be terrible to wean off. And for me, it is just torture to wean off them. Now, again, I've gotten the blessing from him that I am “cured.” If we want to talk about that, I put it in quotation marks. So it's not that I haven't recovered, but I am still on medication. So I don't change the dosage at all. It's been the same for however many years now, four or five years. It's like a maintenance thing at this point.

Someone might argue, Oh that means you have it. But just because you take medication doesn't mean or a pill doesn't mean that you have something wrong with you. I take vitamins and I'm not vitamin deficient. You know, I take vitamin D and I'm not actually vitamin deficient. So that's the way I think of it is no, this has just become something that my body is dependent on. And it's just not worth it for me to try to, titrate off them at this point.

I might try at a later point, but you my mother just passed away and it was, like that, I don't want to now at this point in my life start titrating on my own. That doesn't interest me. So it becomes, it's like a vitamin. I just take them and I know that so many people have been wronged by medication and some people would say it's not medication, it's psychiatric drugs. And so I don't mean to be light about this or to say, yes, they're just like a vitamin because that's not what I'm saying. But you get the idea. I'm just making the parallel that taking a pill doesn't mean you're sick. And so, yeah, to your point. So now I guess that's why because of him, he's also the first one who spoke to me about recovery. I had never heard of mental health recovery. Not once in 25 years had anyone said you can recover. Never.

And he and I were in our session and it was apropos of nothing. He just started telling me about a client he had who had schizoaffective disorder, which in the culture is one of the worst diagnoses you can receive. And he came to see him and he worked with her and he wasn't trying to call himself a healer, but there was a different reason he was telling the story. Long story short, she had recovered and gotten off all medications and had become an executive at Google. And I thought, first of all, you do not recover from the schizoaffective disorder or anything else. You do not come off net medications and you do not become an executive at Google. So “Google executive” became the pinnacle of mental health to me, which is so hilarious to me now. I do not want to be that, but once he said it, I thought, wait, I can recover?

And then my second book, Cured, which is serialized on Substack and available for everyone to read, that really became, again, because I'm a researcher, it became an investigation into the recovery movement. We've been recovering from mental illness and serious mental illness since the 16th century, but no one talks about it. And so that's how that all came to be. And then, of course, I'm not as angry now.

Kimberly

Well, you had a book to write through all that anger. And I love that you channel that through all the research too. I mean, I can almost picture you in those moments—we need to do something with that emotion, and it was very productive for you.

You talk about Cured and that the definition of cure is actually “to take care of.”

Sarah

Exactly.

Kimberly

So you wrote about this in your book and you said, “in that sense you were cured because you'd learned to take care of yourself.” And that's such a different way of looking at being cured. Can you talk a little bit about how this understanding of healing has evolved? I know for me it has completely evolved as well. I am not cured, but I have a very different relationship with my body and with what my expectations are, what that's supposed to feel like, so tell me a little bit about how that is for you.

Sarah

Well, this is where we really come together and sort of dovetail in the way we think about things, I think, and tell me if I'm, you know, misspeaking. If “to be cured” just means “to take care of,” then that's very different than thinking, what does it mean actually in our minds? Well, if cured means “Google executive,” whatever that is, it means “I'm happy all the time and I never have any problems and everything is great and I eat well and I never binge and I'm okay.” That's our view of cured right now, which is totally untenable and unrealistic. The idea, wait, What if cured means just “I'm taking care of myself really well. I'm good.” That's all we got to get to. We don't have to change the world or do anything else. We just get to a point where we say, “I feel mentally healthy, I feel physically healthy, I feel emotionally volatile but solid, you know, because you're a human.”

Kimberly

You’re alive!

Sarah

Exactly. Like I have panic attacks, I have anxiety, I get depressed. I mean, I'm grieving, you know, and really separating the difference between grief and depression. All those things are part of the human existence and, you know, experience and you cannot avoid them.

So if we looked at that as being cured, and again, that doesn't mean you go off medication. It doesn't mean you stop seeing a therapist. That's the problem with this idea of cured. It doesn't mean you stop doing CBT. I do a ton of thought work. I do a ton for my mental health. It's just, Oh wait, I found the pieces that work for me and it's working. I'm good right now. And it's not necessarily, I mean, I don't worry about getting sick, let's just call it or that's how I think of it. Again, I don't worry about that. And it's not that I'm being overconfident or anything close to that. It's just that I know what I was like to get in that situation that I was in. And again, it was not my fault. And I just have too much knowledge now. And as I said, I'm too empowered. Doesn't mean I wouldn't go see my psychiatrist and be like, We gotta talk, something's going on. Then yes, I go get the help I need. But again, that feels to me cured. I can get the help I need. I can do what I need. So yeah, that's how I see it.

Kimberly

The word that comes to mind as you're talking is tolerance. It feels like we, in a way, to be able to take care of or to feel cured in the sense that you're talking about it, is that we develop this hearty tolerance for uncertainty, for feeling like shit, for having a bad day and needing to go get the resources, finding the resources. Like, it's just more tolerance—not going to this catastrophic place when shit hits the fan and instead, Oh it's a bad day or Oh I need help. I don't know. It feels like tolerance is such a huge part of my own growth in this too, where before I wanted to feel perfect all the time.

Sarah

Yeah, exactly. And again, I know the difference between and you do too, which is that being and I don't mind the word sick, being very ill. And I was very ill sometimes. And once I think of mental illness as a spiral, that once you're in it, and after a certain point, it's just feeding itself and it's very hard to get out of that place. And so I'm very sensitive to that, to anyone listening, like, this is not easy. I'm not trying to make it seem like any of us ever weren't doing what we need for ourselves. We were doing the, I was doing the best I could at that time. And once you're in kind of, you're under it a little bit, it's very hard to get out from under that. But once you are, and you can slip back in and all of, all those things are real and can happen. But to your point, the thing that helped me the most was actually evolutionary psychiatry.

It was the most helpful way of me. It changed my life. Once I learned that we are literally designed to be afraid, to be anxious, and possibly to be depressed, changed the way I see things. So in evolutionary psychiatry, you know, again, we are designed to run from lions on the belt. So yes, we're only opening email, but if we're anxious, we're like, I'm going to die from this email. Absolutely. Now there are truly times when you are gonna die so it's good for us to have these mechanisms in us because when you're crossing the street and a car is coming at you, you wanna react like that. So noting that my brain is not here to make me happy. It is only here to look out for danger and tell me that everything is horrible so that I'm safe. It's like, stay in your house, stay in your apartment. Sit on the sofa, don't risk anything until we need food and then only go to the refrigerator. So that's basically how my brain works. And once I realized that, that's amazing.

And then depression's really fascinating because you would think, wait, why would we evolutionarily be designed for depression? And Randolph Nesse is a psychiatrist. He's at University of Michigan. And he's the one I've really found as an evolutionary psychiatrist to be just so insightful and a great read too. He has a book called Good Reasons for Bad Feelings. So highly recommended. And he talks about how when you've been anxious, you've been up here—which I know a lot of people listening probably can't see me—I'm saying like, you know what, you already probably know what I'm saying, but you are in that hum or screeching of anxiety, of even mania, because anxiety can flip into mania very easily.

When you are up there, your body has to get you back down. How does it do that? Depression. You've got to depress to get back down. Now, the problem is, as I said, we're living in an environment we were never designed to live in. So we're out of whack. These are, you know, we're not meant to be online at all. We're not meant to be on social media. Nothing.

And that is really just kind of exciting to me in the sense of, wait, I'm actually okay. But it's the society that's the problem. And I want to live here, so I'll just keep going.

Kimberly

And it forces, not forces us, invites us into having maybe a bit more of a compassionate conversation with that part of ourselves too. I imagine like it, when you're like, Okay, well, this is just a well-intended machine. You can kind of talk to it then and go, “I get what you're doing. Thank you for trying to keep me safe here.” It just seems a little bit more like, you know, we talked to it maybe like a child that's just, doing its very best to keep us safe.

Sarah

Exactly. And it really is doing its best. And of course, I can't do that all the time because I get swept up in things and it really does feel like the world is ending. But it is different to be able to at some point say, Oh okay, yeah, I see the parts of this that are a little bit of an overreaction to the situation.

Kimberly

Yeah, yeah. My gosh, I have so many, there's so many different ways I want to take this and I'm trying to be as clear and concise as possible. could think I could talk to you for hours. Let's touch on grief. We talked about anger, but I know that you also mentioned in the early stages of this for you, there was grief. And that is probably so true for a lot of these early diagnoses or later diagnoses, it's just a phase. something that we're going through. We're handling, we're alive, we're human, we're dealing with life. And you mentioned in your book that bereavement exclusion in the early DSMs was actually a thing and how grief was once protected from being pathologized.

Remind me, grief is not pathologized in the current DSM?

Sarah

No, it is! Yeah. So if I grieve my mother longer than a year, now granted, what they're talking about is dysfunction, supposedly, but I think it's actually much shorter. I have to look at it again, but I think it's actually two months or three months. It's really short. It used to be a year and then now it's shortened. It's ridiculous. I mean, you know, and again, the way I react to things is I work.

That's how I deal with things, which is why probably I had bipolar or was diagnosed with bipolar because I can, I mean, there's a difference between working a lot and mania as anybody who's been manic knows, but that is again, why I was probably susceptible to that because that's something I do. Someone else may not be able to get out of bed. My depression was never like that. So my depression did not come in the morning. It came in the afternoon and it's an atypical type of depression if we're going to call it that, which again, mania, depression, anxiety, they have been around since antiquity. It's not like these are not problematic terms themselves. It's the diagnoses that we're talking about.

So depression, atypical depression, the onset is in the afternoon. And that's what's always happened to me. So this is just to say that I work. So I may not look like I'm dysfunctional, but perhaps I am, you know, again, looking at what does dysfunctional even mean? How am I being dysfunctional in my life? It's going to look different for every person.

But I lost my mom in December and, you know, again, it was something I couldn't have ever even imagined. Grief is nothing like I expected it to be in that it's anxiety, it's panic attacks, it's just kind of fascinating actually how different it is. I just assumed I'd be crying all the time. And of course I want to cry right now, but someone told me that your tears actually heal you. Yes.

Kimberly

Right, there's actually chemicals—

Sarah

So I'm not as afraid of it or I don't think anything's wrong when I'm crying. But these aspects of grief that are so fascinating—and so going back to it at the time when, for instance, when I wasn't eating and your friend's son, you've lost something. You just lost a person. I've just lost my parents' marriage. I just lost my home. I just lost my school, my friends. I mean, those are huge losses. And so why wouldn't they affect us like grief?

But anyway, more going to typical grief. What's been really fascinating too about being in this is right when she passed and I had an amazing grief counselor, which I highly recommend for everyone. I also was lucky enough that she was in hospice. So hospice workers, if there's anyone listening, you are angels. You are just absolute the most amazing people I've ever encountered are hospice workers. So that was incredible. But my mom's, my grief counselor said, “You can make this anything you want it to be,” as she was dying. And she said, you can make it tragic, you can make it sad. And none of these are wrong, by the way. You can make it magical, you can make it horrible, you can make it okay. Like she just said, you choose. And my mom's death was really magical.

It's a much longer story. I won't go into it.

Kimberly

I remember you writing a little bit about it on Substack...

Sarah

Yes, I did. Yeah. And it's going to be in my new book. But this is all to say that in the Jewish tradition, my sister had converted to Judaism. So I always joke that I'm Jewish by marriage. But you grieve for a year. In no way do you think you would possibly not grieve fully for one year. And I love that. And so I feel very lucky to be adjacent to that, if nothing else, to be able to say, we're not even gonna judge anything until after a year. We're just not even gonna worry.

Kimberly

You're expected to. Yeah, you should be acting out. You should be disappearing. You should be feeling the whole spectrum.

Sarah

Yeah. And I think too, someone who's listening might say, yes, but some people need medication and that's why we give them that diagnosis. And I just go back to the same thing, which is “Of course,” and I'm all for that. Just tell the person the truth, which is that, “Okay, this came in to the DSM-5 and it's totally, there's no scientific evidence backing it up. We're using it to get you this medication because I want you to be functioning more in your life, but by all means you get to grieve as long as you want.”

That's a healthy conversation, but those are the conversations that aren't happening.

Kimberly

Yeah, I remember Sarah, I was about eight years in—my dad died when I was 18—and I didn't grieve, I did the steps, I went to a therapist and I wrote letters to my dead dad and I did all the stuff, but no one was, I didn't have the type of therapist that could really perceive that I was just putting on a show for everyone and kind of get me to—and maybe I just wasn't ready, just wasn't equipped. Anyway, eight years later, I ended up, my body was breaking down. I was diagnosed with Graves' disease. I was all this stuff. And I accidentally ended up with a job at a film production studio where I had to log all this footage from a bereavement center, 20 years of footage, they were building like an anniversary video for them. So I would sit there all day long, all summer taking notes on all these videos from VHS and BetaCam. And I remember the woman who founded this organization called the Dougy Center. She said, “We don't worry about the kids that act out. We don't worry about the kids that disappear and hide. We worry about the perfectionists.” And I remember just like shivers just rose just as they are now.

Sarah

Yeah, me too. I just got them too.

Kimberly

The pen dropped. And she said, "And the reason why we worry about them is because their bodies break down.” And I was like, My God. But if someone had come along and just allowed that space to be there, it would have been such a different experience. Sure, maybe someone would’ve diagnosed me with anxiety and OCD, but then also explained what was going on underneath that, that might've helped. But with nothing and no expectation other than to just continue forward with life, it didn't serve me at all.

Sarah

Yeah. Yeah. That is an amazing, amazing story. How lucky and oddly that you found that you ended up there. Wow.

Kimberly

Craigslist. It was a Craigslist ad that I answered. I just thought, Oh cool, I'll do this before I start naturopathic school. You know, what fun.

Sarah

You get to revisit everything.

Kimberly

Yeah, whoops.

So speaking of grief, you actually wrote an essay after Pathological, the re-release of Pathological came out and the essay was titled Grief Work and Giving a Book New Life. And you talk about the relaunch and the grief that was mixed in with that. And I just want to talk a little bit more about that. How did revisiting this story affect you in your healing journey?

Sarah

Well, I'll disclose something, but it's just between all of us that will now go on the record. But, know, and again, I love traditional publishing. I'm a huge fan of it. I love, I plan to publish traditionally. I think that they are, you know, those editors, everyone working in traditional publishing really believes in books. It's bit of a flawed system, like all systems. But when my book came out, and I shouldn't blame the publisher actually—really, if I were to blame anyone and anything, it was a pandemic book. We're called pandemic books. And it was really just very hard to sell. So if the expectation is 10,000 books sold, normally they cut it in half for us, which is nice. So I'm a pandemic book. But like I said, we just didn't have the zeitgeist with us in the sense of the media was saying, Get a diagnosis. The media was really you know, kind of pushing diagnoses and probably they had the best intentions as well. It just wasn't done very responsibly. People did not want to read criticisms of diagnoses at that time. And it did very well. You know, we got a great review in the New York Times and, and, you know, it was an Apple Best Books pick and it did extremely well. I mean, it sold way more than most books do. So I'm in the 1 % of books in terms of sales.

But of course I wanted it to have a bigger effect as all people do, all authors do. And so then I was, I don't know if you've ever seen the show, The English Teacher, the sitcom. Okay, I'm not a sitcom person, but someone contacted me because I wrote Cured and my subscribers on Substack all know that, you know, mental health and said, you have to watch The English Teacher. You have to watch episode three.

And so I went, it's very funny, actually. I did watch the whole series and it's basically about this gay English teacher in Austin, Texas, who teaches English in high school and is both baffled by and deeply loving and caring for his woke high school students. And it's very funny. So all these things come up. But anyway, they did it where, and this is going to sound bad, but you have to see it. So in no way am I, I'll just leave out what it was, but a one of the students comes out with an asymptomatic mental illness like diagnosis. And then it's so tragic that no one can see it and it has actually no symptoms. And it's hilarious. So she was making fun of the whole thing and what's happening on social media. And I thought, and then it won an Emmy. And I was like, you're kidding. If this gets away with it and it wasn't canceled, we've hit someplace new.

So the minute I saw that, I decided to relaunch it because I thought there's a whole new audience for this. And that's how it started. And we simulated a pre-launch, as you're getting used to. So anyone who's listening, basically you've got months before the book is traditionally released or officially released to sell it. And all those sales count toward the first week of sales. And that's how people end up on the bestseller list. And we simulated that. And that's how we got on USA Today.

And so, yeah, so was really just looking at, I had grieved my book for a very long time. It felt very sad to me that it did not hit the way I wanted to. I wanted to change the world. I thought, wow, we're gonna just do this and everyone's gonna be helped and saved and empowered. And it just felt like it didn't get there. But sometimes things need two shots or three.

Kimberly

It's clearly the time now and sometimes things just have their own gestation period.

Sarah

Yeah, exactly. You know, part of it too, I'm a journalist and a researcher. I'm not a doctor. And in no way in my book do I do anything like advising or I'm very like I've been in this interview, I'm very, careful about what I say so that it doesn't sound like I'm one giving advice or have any answers, as you said, it's more just let me give you the facts and the information.

But the media is very, very worried about having anyone on without medical credentials. So the mainstream media tends not to have people like me on anymore. So not on any talk shows, not on any major podcasts, major radio. If you're not a doctor talking about mental health, they really don't want to have you on.

Kimberly

They just feel like they could get in trouble. It's all litigious.

Sarah

It's the liability piece. I think, well, one of my friends actually has a huge podcast. And I said, Will you have me on for the relaunch? And he's wonderful. He said, no, because it's not because he doesn't love my book. He said, we just, our listeners drop dramatically unless we have an expert on. And he said, it's how he makes his living. He said, it's a business. It's just a business decision. It's got nothing to do with you.

And that was, so it's also the public that is very much like, Okay, I'm gonna listen to that person, which I get.

Kimberly

But you are an expert!

Sara

Right? That's the peer support that people miss out on, which is there's another side of this, which is what is the patient's experience? And what I find interesting is that doctors seem to be more open to this than the media is. They do, and again, I'm generalizing hugely and I'm sure some doctors are not.

But some doctors are very much interested in what's the patient's experience of this. What has been, you know, what was your experience? Ultimately, that's what hopefully hospitals are doing when they send you those surveys. Maybe not.

Kimberly

Right. Well, have you heard of Health Story Collaborative? It was co-founded by Dr. Annie Brewster. She's a Harvard medical doctor. Actually, she's the one that I collaborated with on the Unfixed Mind docuseries. So yeah, so Health Story Collaborative is based in the research around narrative medicine. Columbia University even has a program now for narrative medicine. So there is a movement of doctors that are starting to recognize the value of patient narrative.

And I mean, so much so that one of their projects is the, I think it's called the Opiate Project, and they basically open up theaters and allow people to get up, patients to get up on stage and talk about their experience with opiates. And they've done their homework to really legitimize the value of this type of storytelling, not only for the patient, but for the doctors and the caregivers and everyone else listening.

So I hope that movement continues to grow. I think there's three programs in the country now where you can get certified or even a degree in narrative medicine.

Sarah

Yeah, that's so great. What's the opiate one called?

Kimberly

Well, just go to Health Story Collaborative. Yeah, and if you want to connect with Dr. Annie Brewster, I would love, she's amazing, really cool woman. Doing a plug for you, Annie!

Sarah

Cool. I'm writing a town, Annie! Everyone else is too!

Kimberly

But yeah, the two of you would love each other.

So anyway I want to talk a little bit about this experience of living in the uncertainty and your whole story, Sarah, has just been one roadblock and curve and bend in the road. I mean, all along the way, since you were a very little girl. And so you've learned to live with uncertainty. So do you feel like through all that, has your relationship to uncertainty changed? And how do you look at it as a positive generative force for our collective?

Sarah

I still greatly dislike it. Greatly. Look at my, so people, if you're watching this, you can see the background. You can see my home, my apartment. People often ask me if it's a virtual background. This is just to say it is incredibly meticulously neat. That is me trying to control the world. that is me trying to be certain where there's no certainty. And that's why my mom's death too, I mean, that's the other thing. It really makes you—that's where the panic comes from. That's where the anxiety comes from is, a second, this is real. We are going to die. What is this? What is this? What is going on? All of those questions start to come up.

But what I am better at, and now I have a business, so I'm still a writer, but I work on Substack. I don't work for Substack, but what I do is I help writers and creators build their platforms and earn an income on Substack using the platform. I seem to have a gift for like the Substack whisperer. It was never a gift I wanted, but I seem to have it. So I'm very grateful because I get to help people like you who are just so talented and cool. But having a business and being an entrepreneur, it's crazy uncertainty. I mean, it is crazy. And I just had this unbelievable thing happen with my business, it just feels like it's the end of the world. And I was thinking this weekend, I could have been completely losing my mind. And I just wasn't. I mean, I did. It kind of went in and out. But I knew when I came out of it, I would think, Okay, yeah, all right. We're just panicking. The world is not ending. There is a long game. Let's just stay in it.

But being an entrepreneur, I'm a solopreneur, I don't have employees, it's just this whole wild roller coaster. And it really is, I mean, most authors are literary entrepreneurs. That's what we do. And I never saw myself like that, but we really are, we have a business, which is our books. And even relaunching Pathological, I was telling you that, you know, here we landed on the USA Today bestseller list and the best USA Today links to bookshop and my book was not available.

And so things like that, mean, I should have been, my friends were more angry than I was. And I just thought, Okay, let's just keep going. So I am much better about it. But I also, know, a lot has changed for me. I think the one thing that we don't talk about enough with mental health is economic insecurity. I spent most of my adult life with no money, like none. And so I was a poet in New York City.

The financial possibilities were endless, as you can imagine. So it was just, now granted, I chose this lifestyle because I have chosen to be an author and write and teach. And those are not, you know, I'm not a banker. I didn't get go work for a hedge fund. I always say to my students, if you want money, work in a bank. If you want words become a writer. And that's how it is. But I am financially in a totally different place than I've ever been in my life. And I know that has a lot to do with my security and my mental health, my emotional health. It's completely different. And I do wonder how many people would suffer from mental illness if we had more economic equality. It would be a very different story, I guarantee. And we don't want to look at that.

And that's part of the diagnosis thing too. And I talk about this in Pathological which is why we depend on diagnoses because we'd have to answer to so many societal ills if we ever said, no, it's not just that. It's all the things, it's all the layers. And there are people doing that, but that's not the first conversation that we have. You don't walk into, I mean, not once did anyone talk to me about caffeine. Not once did one doctor, I'm experiencing anxiety and mania and no one asked me about caffeine in 25 years in the mental health system. I was like, and then finally, finally I quit it. I don't, I mean, that's the other thing, you know, becoming cured has been unpleasant at a lot of the time, meaning I had to cut out flour. I had to cut out sugar. I had to cut out, you know, I mean, there's just caffeine. I don't drink, I don't do drugs. Yeah.

Kimberly

And then you still don't feel and then you still have bad days. There's no guarantee.

Sarah

Of course, yeah. But those things alone, I eat in a way that most people, one, couldn't afford to, two, don't have the luxury of, you know, three, aren't being helped that way to create a diet. They aren't even being talked to about their diet or, I mean, just, you know, soda, like soda, like period.

Kimberly

Yeah. How does a doctor even begin to go to all of those layers, even those you were just mentioning, are still within somewhat of the personal sphere. But then you step outside of that into the socioeconomic world and the air that we're breathing and the stress that we're feeling and the screens that we have to be beholden to. I would imagine it's enough for any psychiatrist to just throw up their arms and write a prescription.

Sarah

And I can't imagine what doctors go through. And that's part of why I don't, I'm not anti-psychiatry. I'm not anti the medical establishment. I don't think our mental health system is horrible. I think we ask a lot of psychiatrists. We're coming to them and psychologists and all mental health professionals, we're saying Here, solve my mental and emotional pain. That's not easy to do. We don't have a way to do that. And so they are doing the best they can. I don't think they're—I mean, again, I don't know everybody. I haven't done a poll. I haven't done a study, but I find it very hard to believe that the people dedicating themselves to this have ill intentions. It just, even if they might not be what I want, I think everyone believes they're doing good. Even the people who are pushing the DSM.

I love Tom Insel, who's really just been a huge supporter of mine. And I'm so grateful for that, but he was head of the NIMH for 20 years. And spent, I think he says, sorry, it was 13 years. And I think he says he spent $20 billion on really cool studies with brain imaging and all of this. And he said, “and we didn't move the needle at all.” Not at all. So he's come out. He has a wonderful book called Healing: Our Path From Mental Illness to Mental Health.

But Tom Insel is his name, highly recommended. And he came out in that book and really did a mea culpa in a way that very few people, professionals, adults would ever do, which was he says, “I blew it. I made a mistake." We do not have a biological basis for any diagnosis. And I spent all my time looking for one.”

And he tells a great story about giving a talk. And he's shown all these great brain imaging pictures. And this is what we know about schizophrenia and dah, dah, dah, dah, and it ended and a man stood up like they were taking questions. And he said, You're telling me the composition of paint and my house is on fire. Like you are not helping me. Like, my son lives on the street. He has been diagnosed with this or, you know, and he's now turned to drugs and you are telling me the composition of paint and not telling me how to put out the fire in my house.

And Tom said it changed his whole perspective, his whole life. So he's come out and again, so this isn't just me saying this or anyone else. This is Tom Insel who was head of the NIMH. This is Alan Francis. He authored the DSM-IV. He has said these are completely out of control. He actually had a great piece in the New York Times about autism because RFK is, he's making all these claims about autism. And what Alan Francis is saying is he said, No, I widened the criteria for autism. I am the reason why so many people are diagnosed with autism. I'm telling you, I am the reason. And still people don't want to listen. And it's really fascinating.

Kimberly

Sarah, so there's a movement happening. You are on the wave of this movement. What would you say to the young people that are suffering, that are on TikTok looking for answers, but not feeling any more empowered as they find them? What do you most want for that young population?

Sarah

It's, I became a peer recovery specialist and now I am not on the front lines. So just know that I want to be honest. I did, I did a lot of that, but at one point, um, you know, I was speaking to some, a young man, runs an amazing, uh, youth mental health organization in Oregon. I mean, amazing doing great work. And I went to him and I was so excited to talk to him about recovery. And he said, Oh no. We don't want to recover. And he was saying young people don't want to recover. They love their diagnoses. We want to hold these diagnoses. And I would just say, I get that completely. I held mine so tight. And if you had, I mean, even when I started to move away from identifying with the diagnosis, I clutched them so hard.

I'd lived my whole life believing this, I spent 25 years of my life making decisions, being in relationships, choosing what to eat, doing this and this according to a lie. You know, that it was a lie. Those things aren't real. And so I would just say that I don't want you to wake up 25 years from now and be as angry and feel as much loss as I did, which is just to say, use the diagnosis for what it's worth, but it is not you. You are not your diagnosis. And as much as it might feel like, Wait, this gives me an identity, you are so much more than your diagnosis. You are so much more than that. And I think that there are rare cases where it doesn't limit people, but for the most part, someone is telling you that you are not whole, that something is wrong with you. And that can only be limited.

Kimberly

Yeah. Wow. That's such good advice. And it almost it's like it's, it's if you are diagnosed, see it as, an opening, not an ending. Like this is the beginning of the story. And now the bulk of the story is doing your own personal investigations and relating to who you are, getting to know who you are and then relating to who that is without the labels. Just be surprised by who you find waking up in that bed each morning.

Sarah

Totally. You know, just going back to certainty and uncertainty, I think that to some degree, and I'll speak for myself, the label felt certain. When I could not control anything and I did not know what was happening, I didn't even know what an emotion was. I didn't even know that emotions are sensations in our body. No one told me that. I did not get the memo. So, and we don't really teach, we don't educate about emotions.

And so, again, I think the diagnosis feels like certainty when you are feeling very uncertain and scared. And it's not, actually. It's a false sense of certainty.

Kimberly

Yeah, absolutely. And it can stop you then from going and investigating those emotions.

Yeah. Wow. Sarah, this is part one. We've got to continue another because you're writing a new book. You're in the process. And can I ask what it’s about?

Sarah

Yeah, yeah, yeah. It's very different, but not completely. So it's still very researched, but it's looking at, and this is something I'm very fascinated with because, you know, and this goes to everyone. I'm a very solitary person. The main contact I have or social life is my cats, pretty much.

Kimberly

This is why I love you.

Sarah

And so, but there's a lot in here that what I'm seeing and all these ways that people are trying to be happy and this and that and Instagram is that we don't value non-human relationships enough. So not just animals, but objects and nature and fresh air. And, you know, looking at all these parts of us that or all these things that are around us that if we saw ourselves as having a relationship with them, instead of “I own my cat, I own that chair,” that's not a relationship, right? In the way that we think of human relationships. But if we extended our definition of human relationships to objects and to nature and to fresh air and all these things, we might have very different human experiences. So that's the new book. And then death at the end.

Kimberly

Okay, I am just biting my tongue because this is the conversation I have with my husband all the time. All the research that keeps coming out is like, “to age well, you got to have community, you got to have people all the time, you got to connect with people.” I'm like, I am so happy, so much healthier than I ever have been. And I don't see a soul other than my cats and my husband. And then these exchanges, you know, on Substack, which is a beautiful community, but you know, it's virtual.

My connections and my relationships are with nature. And I'm so tired of this research that's telling me I'm going to die young with dementia!

Sarah

Exactly. And I don't believe it either. And we're also obsessed with romantic relationships. Nope. I think it's wonderful when you have one and you find your person. And again, I mean even just sex, that as being somehow fulfilling because it's a way of being closer, which I don't really agree with necessarily. But then also obsessed with friendship. Obsessed with you have to have so many friends and you have to go to brunch and you have to do these things.

And it's absurd. It really is. And I love that you said that because that's who the book is for, is really to help people who feel like, wait, this is not even comfortable for me. I don't even want this.

Kimberly

Yeah. Wow. I'm so excited. This is great. Okay. Well, part two coming.

Sarah, thank you so much for sharing your brilliance with us, with me. Boy, I'm thrilled that this book is out there and I'm thrilled that you are just, you're a firecracker and you've got so much to share. So thank you.

Sarah

And everyone listening, I'm gonna have Kim on my live. So for when your book comes out, which I hope everyone is buying pre-orders like crazy. And I'm very excited for your book to come out.

Kimberly

Yay, thank you, Sarah.

Thank you both for a very inspiring and educational interview. Pearls of wisdom;

“I am not my diagnosis”

“I had been seeing a psychiatrist who was also my therapist. So he was playing both roles, ill-advised, everyone listening, ill-advised, because you don't have anyone to talk to about your psychiatrist and no one to talk to about your therapist”

“mental health recovery”

“I thought, wait, I can recover?”

Such an amazing conversation. Sarah’s thoughts on the issues with the DSM and the way these categories, while helpful for some, can also be unhelpful or even harmful for others — is such an important and powerful point! And being as someone who has his own problems with labels and categories, that stuff really resonated with me.

Thank you both for an illuminating conversation. :)