Rebekah's words take me to the wordless

If you can get down to the truest, most specific heartbeat of your own story—the one you think only you know—it will unlock something universal.

There are words that are labeling and describing and organizing. And also there are words that are like conduits to our bodies or ways to connect, like tools or little prompts to try to move beyond language. I mean, if that's possible—language that helps us move beyond language.

Rebekah Taussig, PhD, author, disability advocate, mom

Some people arrive in your world like a springtime inhale: fresh, warm, and alive with promise. Their presence stirs something unexpected. Expansive. Playful. Like fairy dust scattering enchantment and planting possibility in every encounter.

Rebekah Taussig is one of those people.

You may know her as the author of Sitting Pretty: The View from My Ordinary Resilient Disabled Body—a luminous, layered memoir-in-essays that has gently upended and reimagined the disability narrative space. But she is so much more than her bios suggest.

And honestly? I couldn’t dare try to describe her better than she already has:

I am also and forever the restless daughter of Good People. A scrappy misfit. A daunted optimist. A teacher without a classroom. A poster child for imposter syndrome. A mother bewildered by the idea of Mother. A storyteller who can’t stop herself from turning the thing over and over and over, looking for the parts that are hidden, hiding, holy.

I peek over the edge with wonder and terror. I live in a body that announces its difference, its misalignment with the world. A body that suggests it has no secrets, while holding a whispery trove. I listen to crime podcasts and make angel food cakes, hold onto anger and clothes with holes to mend.

I can’t see the either without the or—can’t hold onto one without reaching for the other—always both/and. My body feels life as bleak and beautiful, a ragged edge with a deep inhale of joy. Always the same, always always shifting.

In this conversation, we talk about her journey from writing fiction to creative nonfiction, the slow revelation of disability as identity, and the ache that comes with always being expected to teach. We talk about what it means to be seen first as an advocate when you’re both an advocate and a writer. A storyteller. A builder of worlds with language that brings the hidden out of hiding and into the holy.

We also talk about grief. Motherhood. Aliveness. The pressure to produce—and the freedom that comes from writing what no one has asked for. The body as archive and oracle. The ways we slowly return to ourselves—again and again—through story.

This conversation moved me deeply. I hope it offers you that same sense of something quietly stirring—like a seed of truth buried deep within you finally cracking open. As Rebekah shares in this episode, her mentor once told her: if you can get down to the truest, most specific heartbeat of your own story—the one you think only you know—it will unlock something universal.

That’s the kind of storytelling Rebekah practices. That’s the kind of storytelling that lingers.

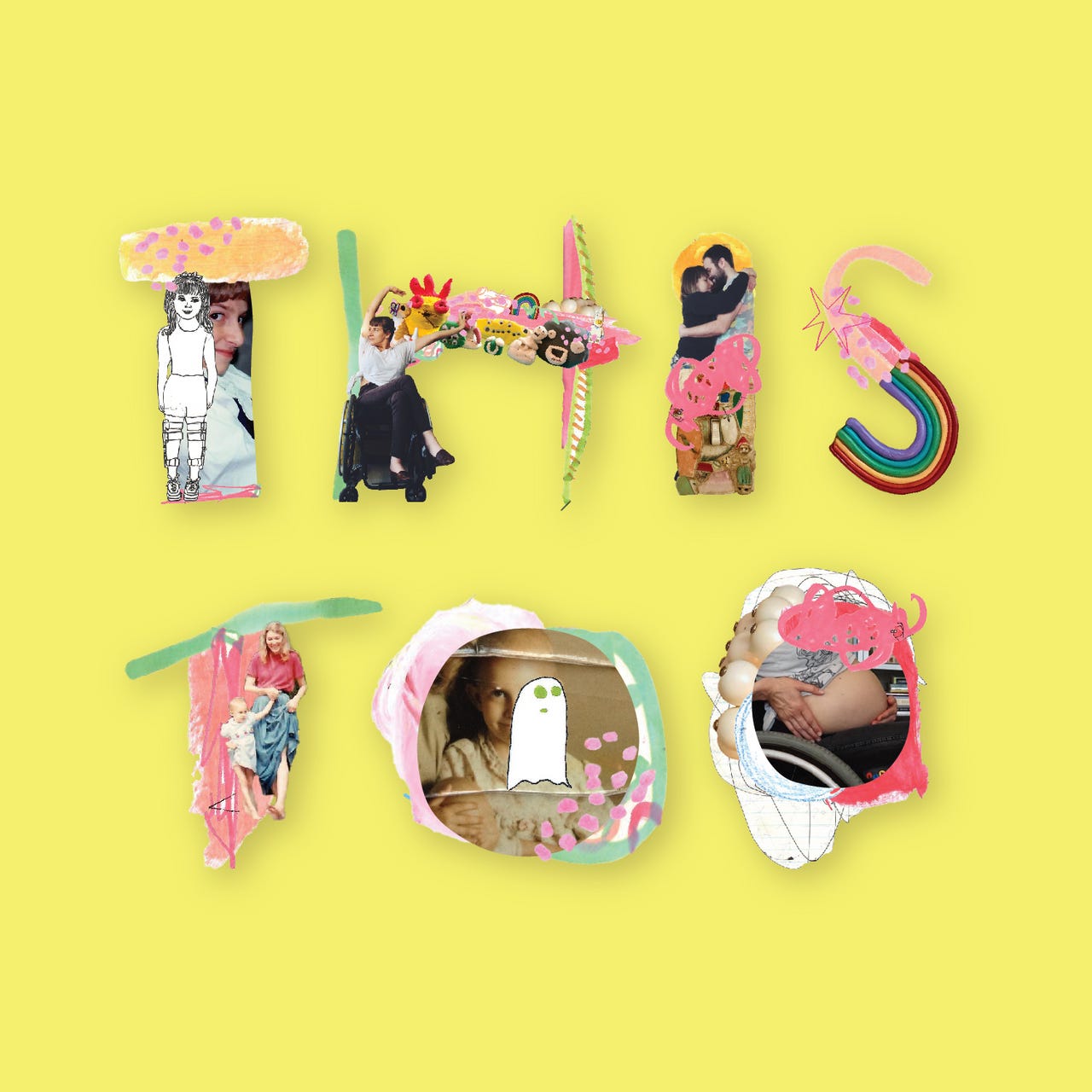

If you don’t yet know her work, may this be your soft landing into it. Her newsletter This Too is a balm and a bright spot in the noise. Her voice—on the page and in your ears—is the kind that stays.

Thank you for being here.

And thank you, Rebekah, for reminding us what it means to be gloriously, unapologetically whole.

(And I must add, you rock pixie-bangs like no one else can.)

TRANSCRIPT:

Kimberly

We're here! My god, Rebekah, your face just sparkles, by the way. When I see your face, I'm just like...

Rebekah

Is it my makeup? I put sparkly glittery eyeliner on my eyes?

Kimberly

I think it's energy that's just pouring out of you.

Rebekah

That’s a nice thought.

Kimberly

So for those of you who don't know Rebekah, this is just such a treat today. Rebecca, I was first introduced to you through, I think it was through our friend and disability advocate, Gustavo Serafini. And then your powerful, memoir-in-essays Sitting Pretty, which, please everyone just read it. It is heartbreaking, redemptive, so deeply confiding and honest.

And then that spun off into your thought provoking reflections on Instagram and then your Substack, which you read out loud. Which—Oh hello, my cat just decided to join us—

Rebekah

Yeh! Kitty!

Kimberly

So everybody, I feel like there's some gold-spun magic that's missing in your life right now if you haven't read Rebekah.

Rebekah, when you write, I sometimes feel like I'm the only person you're speaking to in the world. It's as if we're sitting on a park bench under a tree and I'm the recipient of just this generous, like I said earlier, curious confiding honesty. And the curiosity is really, really front and center for your internal life and then how that interfaces with the world.

For those who haven't been lucky enough to be immersed in all things Rebekah, she is a writer, a teacher, a mom, and yes, also a disabled woman who brings immense clarity, nuance, and humor to the way she writes about disability, identity, and what it means to be human.

So I want this conversation, Rebekah, to go a little bit beyond what you're often asked, to talk about your writing as an embodied practice and the tension between being seen as an advocate versus being seen as an artist, which I think you've written a lot more about lately and how we find the courage to tell the stories that feel most alive in us.

So maybe this one will be a little tender. I already cried before we even pressed record, but I know this conversation is just full of the kind of depth I think we're all craving right now. So let's just settle in and listen to Rebekah. Hi.

Rebekah

Oh, hi, I am feeling my own eyes well up as I'm listening to you introduce me. I think just to feel really seen, like the values that I hold dear being recognized in you and witnessing that and the things I'm trying to make means a great deal to me and having you value those as well. Curiosity, I think the intimacy of digging into questions in a way that feels hopefully personal, all of that matters to me. So thank you for recognizing that in me and for taking the time to sit with that and be present with it.

Kimberly

Yeah, and we'll explore it together today. So I want to talk a little bit about your writing as embodied practice. And I know you've written about sort of the alignment that happened when your writing turned towards your own life and your body and something kind of clicked into place for you. Can you speak to when that happened or why that happened and then what this alignment feels like for you as a writer?

Rebekah

Yeah.

Yeah. Thank you for asking these questions about writing. You're being very generous to me. I feel like you really read my recent essay on grappling with am I a writer or am I an advocate and not getting a lot of questions about writing. So you are just giving me little gifts to open. Yeah. Okay. So I guess I would start by saying that writing has been, I don't know, an extension of my being for since I was a child. Writing, gathering little books and making my own books with like computer paper that you have to like rip the perforated edges off of, you know, like gathering words together in collection. And I made like a little library with my sister of all these books we were making. And we made our own library cards and I would write song lyrics and poems. And and as I got older fiction and I was often in retrospect, looking back at my writing, I was often writing about outsiders, people feeling like they don't belong, people questioning where they would fit or why they don't fit. I would write stories about interventions that happened in hot air balloons. And I would write about fantastical worlds where children were sacrificed to community soup every year, just strange things.

And I think a lot about this story that I wrote—that was actually grounded and then a little bit more of reality—of this young woman who finds herself in this very fancy wine and cheese party and she doesn't know what to say and she doesn't know how to act or where to stand. And she ends up busting out of this party and throwing her shoes off and running down the sidewalk right after the sprinklers or right after the sprinklers went off. So the sidewalk was wet and she's running down that sidewalk, escaping that sort of pressure and feeling of unbelonging.

So I'm writing these stories. And even then, like I end up going to graduate school where I sort of shift more towards like literary analysis and I'm writing, you know, about like Victorian literature, but I'm still sort of pulling out these themes about outsiders and people that are seen as unfit or not normal. And when I was in graduate school, I discovered Disability Studies. And so I guess in the background of all of this is to say that I have been paralyzed and used a wheelchair since I was a child and embodied that reality without a lot of reflection about what it meant to me or how it impacted who I was or how I felt in the world.

And I would even go farther to say that my introduction to the world in this particular body involved a lot of sickness. I had cancer as a child, so was sick for years going through chemo, radiation treatments, recovering from surgeries, one surgery after another. And I think for a lot of reasons that led to sort of a disembodiment in myself. That there was a lot, I was feeling there were a lot of stories that my body held that I didn't quite have access to for one reason or another. And finding Disability Studies in graduate school was a little bit like, I've described it—I think a lot in metaphors—I've described it before, almost like I had lived my life on stage and somebody turned the lights on and I kind of recognized where I was and who was in the audience and what part I played in that performance on stage. It was very clarifying for me. It gave me language, it gave me a framework for kind of understanding myself. I think that was the beginning for me of learning to acknowledge that I had a body and what it felt like to be in it. And so that sort of new lens, that new alignment, started to show up in my writing. My writing is an extension of me, right? So it started to show up and I started to realize like, oh, I've been trying to tell a story for a long time. And I didn't know how to get there. I didn't know how to access that. I didn't know, I don't actually know what it feels like to run on pavement, concrete, wet pavement, right? I don't actually know what that feels like, but I do know what it feels like to try to get my groceries in my car fast enough so that nobody will feel like they have to come and help me to try to show the world that I'm capable of doing this thing. Or I do know what it's like to shut off my access to my own pain so that the nurse in the room is more comfortable. These are things that I do know. And so I started to lean into that more. And I think what happened was that my stories felt truer somehow. And that's not to say that nonfiction is somehow truer than fiction. I think it was for me, it was a block that I had of like, what is the story I'm really trying to tell? And I think for me, it required being more connected to my body to know it and to tell it. So that's a meandering way of maybe saying that was a little bit of the journey for me.

Kimberly

Yeah, no, that's that that is the journey. And so I think we have to meander to get there. And the embodiment that you talk about, we can't take that for granted. We can't just assume that that's going to be informing our craft. And it sounds like it really was a process of turning that stage light on to recognize your place in this world in order for it to come home into you.

Did your writing change at that point then?

Rebekah

Well, in really concrete ways, it was the first time I started writing nonfiction, like personal creative nonfiction. So I was writing, I mean, often slipstreamy magical realism stories, which I still really enjoy and appreciate and will probably return to at some point. But in a practical, tangible sense, my writing moved from either fiction or literary analysis to nonfiction. .

I think that part of what shifted in that beyond genre is just like an immediacy. And I think also I noticed inevitably that like the stories I was writing seemed to mean more to the people who read them. Yeah, which is slippery. It's interesting. There's like there's a couple there's layers to that. But and I think sometimes I think about that in terms of like, Is the thing that is resonating for people the fact that somehow this is a truer story? It feels like a truer story to me. And I don't know that there's any math equation we can do to figure out exactly what that is. But I definitely noticed it. And it definitely fueled me to keep doing it.

But I still have to remind myself, I'll sit down to write something for Substack. And often I'm so in my head and all of it is my ideas and this is my concept and this is my metaphor. And it requires a certain muscle and like a practice of returning and placing my body in that scene and paying attention to what my body is doing. And I have tried to reinforce that muscle in just my like daily writing practices. I have like one of the most, I don't know, like doable things that I've set up for myself is that I have these giant calendars on my wall, like giant—every single day is present on that calendar and each day is like an inch by an inch, like a tiny little square. And every day I will sit in front of that calendar and I will write one embodied moment from that day that I wanna hold on to. Like a sensory, visual, like the sounds, something to capture a sensory moment from that day, and I think of that both in terms of a record like I want to have that record but I also think of it as a way of priming my mind to be present and pay attention to where my body is and what my body is receiving and what my body is telling me through its goosebumps or its lump the lump in my throat or whatever that thing is.

Kimberly

That's so beautiful, Rebekah. I'm picturing, that could almost be an art installation in and of itself, zooming back on your month of April and these moments of embodiment, you know, I would want to like film them and then have it, you know, displayed so that this, it's a full sensory experience for people that are viewing and reading it. I don't know. It's just, that's such a cool way to capture your experience. And actually, it sounds like you're cultivating that presence the more you do it.

Rebekah

That's part of the hope of it. Like I, I have struggled so much over the course of my life. And I think you would notice as like other essays I've written on Substack, I've struggled so much to stay present and to pay attention to what my body is telling me and stay tethered and present. And this is one way that I've tried to build that into my life in a way that feels doable. I mean, I also have like, journals where I'll try to do 10 of those a day. And that practice comes and goes, because that can be a lot. But the calendar one is one that has lasted, I think I've been doing since 2022.

Kimberly

So it's interesting because when I read you, I feel, like I said, like I'm the only person in the world. So you're putting me in my body when I read you, absolutely. So it's, and then you also said that like when you started to do nonfiction, it felt like maybe people were deeply emoting their own experiences, sharing their own experiences because of what you're reflecting. So it's interesting to me that you, that maybe you aren't experiencing that as much, but it certainly is coming through or it's transmitting itself almost onto your reader.

Rebekah

It takes effort. It definitely takes effort on my part. It's not instinctual, but I love hearing that that makes you more present with your body. I mean—

Kimberly

Oh yeah. I mean, your stories about you and Otto, your son, Otto, and the details of the way that the two of you interact. I'm not a mother, but I when I read your experiences of being a mother, I think if I had been a mother, it would have been similar. Like I have these like these just these tender moments when I read you and it's just like, they're just so true. Yeah.

Rebekah

Wow. wow. Kimberly.

Kimberly

So, so I, here I go again. (tearing up)

I want to talk a little bit what that was like for you because when you wrote Sitting Pretty, you know, it's a smart, remarkable story, a memoir, and this was about your disability. And then people were wanting to ask you more about the disability than the writing itself. And so how do you hold that tension between being seen as a disability advocate, but also a writer? Because both of them are true, but definitely not synonymous.

Rebekah

Hmm.

I love this question.

Also, I just want to pause over your tears and just say like you're I, I think that that is beautiful that your body is marking the moment of meaning for us and saying like this matters to me. This is tender to me. And I, I don't know. I just witnessed that with like some awe and wonder at how our bodies speak, you know?

Kimberly

Yeah, totally. My body speaks so much louder than my mouth ever, so I'm glad there's a platform where both can be present.

Rebekah

And we can pay attention to it value it. And yeah, yeah.

Okay, I will say this question is everything to me. am so, I could talk for the rest of our time together about it and I'm quite, I continue to be quite tangled. I feel like every time I try to speak, I feel my words like whip around and tangle back and get, so we will do our best to plod through this. I mean, I think it is interesting, and makes a lot of sense to me why people have responded to my book the way they have and wanted to talk about the things that they do. It makes so much sense, right? That's what the book is about. It's about disability and it provokes, I think, a lot of personal questions for people, both who are disabled and not. And also, I just wasn't quite expecting it. And I think it's in part because my program and the schooling that I'd been doing and the way I'd been thinking about myself had been so writing focused. I had thought of myself so much as a writer and I wrote the book thinking of myself and my work that way. And people will say, I mean, the essay that we're referring to, I think I titled it like, Am I an advocate or a writer and why do I feel like I need to choose? And a lot of the responses to that essay have been something along the lines of like, Well, you're both!

Which is true! Absolutely, I write and I advocate and those things are both true but I think for me a lot of why that question has felt pressing is more internal of when I sit down to “do my work.” (I'm putting air quotes around that.) When I sit down to create something put something into the world I I want to know how I'm orienting myself and I think when I wrote sitting pretty I was orienting myself as a writer who has a particular point of view, who is going to tell true stories about the world from that embodiment. And what ended up happening was a great deal of advocacy in a way that I think is and has been really beautiful and has humbled me and excited me. But I think it kind of goes back almost to that moment we mentioned before of recognizing, oh, this means something to people.

Oh this this kind of story generates this kind of reaction and becoming more aware of an audience. As someone who is so prone to look to the faces around me and ask, What do you want of me? And how can I give you what you want? It has been confusing. It's just been a confusing stretch for me in trying to figure out what I'm doing when I sit down to write something.

And also the complexity of feeling like the mandate to be useful. If I'm going to put my energy into something and if I'm going to ask people to read it, it must be useful. And I think that that leads to a set of mandates that can, I don't know, it's almost like it is undermining my ability to do the very thing that I want to do in some ways.

Here we go getting tangled. I'm getting tangled in these ideas.

Kimberly

I love being tangled.

Rebekah

Okay. All right. Let's be in the tangles together Kimberly. I, I think that there is this way in which if, if I am so tuned in to what this audience, I perceive that this audience needs of me and what kinds of stories I should be telling in order to be useful enough to people, that that can really stifle the witnessing, the telling of a whole life.

And I think in some ways, counter-intuitively, that can stifle the advocacy itself. Like if I think about even in my son's generation, he's five, but thinking about the pictures of disability I want them to have around them. I want them to see a disabled woman who is an advocate and also so much more and doing and telling all the things. And so I think what I have kind of been settling into is this recognition of pushing out my creative edges and trusting that there is value in that, that that is useful enough. It will be useful if it's true and sort of letting my idea of what advocacy is or what it can look like expand and be more nuanced and show up in lots of different ways. And I can kind of play with how I bring that into the world and trusting, like I think some faith there that that will be doing something good for us.

Kimberly

Yes, yes, yes. I think the trust is key, which is hard because the world is going to be using its own benchmarks and its own expectations. You talk about this in your recent essay in Time magazine, which is another one that's just, I mean, everybody has to read this. I actually am going to read a quote that I love from that.

You say:

I'm weary of a world that decides my brand for me. Sees my body and expects explanations, solutions, one kind of story about one kind of thing. And also we can't belong in a world where our inclusion is up for debate. It can feel almost impossible to embody both of these realities at once. We trade one for the other, erasure or spotlight. I don't see you as disabled or I follow you to learn more about disability.

And what I heard in that essay is just the longing to know Rebekah’s essence, like the deep, deep, deep down spark that has not been influenced at all by the world's expectations. And all of us, maybe we long for that. But I think for you, there's been a real pressure almost. And it's like, there's also just this original voice that Who knows, I mean, maybe you're just some sort of erotica novelist

Rebekah

You saw me! You see my deepest self, Kimberly. How did you know? Just waiting to unfurl.

Kimberly

Exactly! So is there anything that's helping you kind of shift from this feeling of being beholden to a brand or an expectation, but then also honoring what feels alive in you?

Rebekah

Yes, yes, yes, yes. yes. I don't know if this will resonate for anyone else, but I do feel like the particular questions that I have been asking are in large part a result of spending a lot of time on Instagram and kind of growing and developing as a writer in a space that is run by algorithms and I think can really create this... it didn't always, but in my perception of it, of start to create a flattening of stories. At the beginning, I feel like it was an opportunity for telling our own stories and those being rich and plump and complicated and somehow over time—and I don't know if it's algorithm—I don't know. I don't know exactly what it is, but I think sort of this flattening experience. And I think that's part of where I started to have a more narrow idea of what advocacy looks like. I think there are certain kinds of “content” that, and I'm using air quotes here, do better in that space, right? That are so quantifiable as shares and likes and you don't even really know if someone even read what you wrote, but you know that they at least heard of it. And so I think that part of the dynamic or the binaries is that I started to have in my mind of writer or advocate or writing about disability or not, sort of started to be created in that in that mechanism in the in that machine. And so I would say just practically, I really do believe that shifting to Substack has been a really good move for me. It doesn't feel like it's operating under the same mandates. There's more space. It's slower. And I think that that can sort of allow for more nuance in a quote unquote brand, if that's even a word we want to use.

Kimberly

Yeah, well, your name, just your name as a writer is the brand then and not necessarily what you're tagging yourself to. At least that's my experience. And I think what you said, even in that Time article, it's like this part of you knows that if you veer, if in that, in your Instagram feed, you wanted to maybe write about cats, people would be like, Well wait, this isn't right. And then you lose people reading because—

Rebekah

Or they literally won't even recognize that it's you because, you know, like they, it won't even, it won't catch the momentum of the algorithm and therefore people will literally not even see it. I mean, it's an interesting game. But I do think also in writing that Time piece, I think, I just have a way of thinking about it that has started to help me figure out or have a little bit more of a grip on like what it is that I'm doing and the value of what I'm doing. Is the difference between being caught in a constant state of reaction and like sort of almost—like I'm caught in somebody else's story and I'm constantly trying to revise that story as opposed to feeling the ground beneath me and speaking from where I am and telling my own story, if that makes sense. I think that my experience in Instagram often sort of beefed up a reaction muscle and an immediate reaction muscle also, like a quick reaction muscle.

And I think that there is a certain amount of value in that. I think that there is value in engaging with the narratives that you see around you or the problems in the world you see around you and speaking to that and naming that aloud. I think that is important, but I think if that's the only thing that we're doing or we feel allowed to do, or the only thing we think is useful, I think there's something that gets missed. And there aren't roots being planted somewhere else.

I think a lot about imagination and the power of imagination. And I think about what world I want my son to grow up in and how I want those kids to understand disability. And I think about building roots into the world I want to exist with them while I'm simultaneously pushing against whatever I want to correct in the world around me. And I think it's like both of those things at the same time.

This is very abstract way of thinking. I hope it's translating.

Kimberly

Yeah. I keep going back to your board because you keep using the word root. And to me, I was thinking of the word anchor, like these embodied moments are anchoring you in truth, in your truth. And it's like that essay that you wrote about your son and not wanting to do like a formal disability lesson for his preschool. And instead of telling the experience of disability you wanted to show the experience. And I think that sounds to me, it's similar in the sense that you're just trying to anchor, you're anchoring what's true today, because it might be a little bit different tomorrow, depending on how you are or what circumstance you're in.

It reminds me I'm working on a film called Unsung right now with the queer-identifying population, 4 individuals. And they talk about labels a lot and how, Yes, they set us free, essentially because they give us sort of this, they project a longing for community and bring that community together, but they also completely can box. So it needs to be recognized that both is happening.

So how do you show instead of tell in your writing?

Rebekah

Well, yes, I think actually you're just like handing me in your question, a little bit of an answer to the wrestling that I've been doing because I think it is bringing people into a real life experience, the moment to moment, without it always having to end with, and here's the lesson, and now you know these three takeaways, and here are your action points. And I think that that kind of storytelling is genuinely transformative. I think that that gets to, I mean, it's interesting to hear you say that you feel more present with your body when you read my writing, because I think a lot of times the goal is to not just change some language in our brain, but feel something with someone and that that is deeply transformative to us. I think that's deep lasting learning. I think that's how we shift. That's the way that we shift our perception in the world is by experiencing it with someone.

As opposed to, I mean, I think lists can be helpful. I definitely interact with lots of people who want the practical, like, tell me what to do or tell me what to say or not say. And I understand the purpose of that, but I tend to think that this bringing you into my lived experience, this moment of shame or liberation or confusion or joy in this particular body is deeply transformative in how we understand each other, and how we might conceptualize something like disability or motherhood or whatever that thing is.

So it's interesting to think about language. We were talking before we hit record about like the power of language and how language has this power. I mean, it's incredibly powerful in its ability to connect us. And I also, at the exact same time, I also find it to be profoundly limiting to being able to actually describe some of these things and how it's like this both and of like, this is the most powerful tool we have. And also there's an edge to it where there is experience that goes beyond it. Cause I think about those labels you're talking about of like, these labels are way of understanding where we fit in the scope of humanity. It's how I understand myself as an individual and as someone connected to a community. And yet, what can you really hold behind that label? How much of a human life can really be expressed through that label? And I think both of those things are true.

Kimberly

Yeah, it's so fascinating—to share with the audience, we were talking beforehand about how much connection I've experienced through the Substack relationships, like deep, deep, deep friendships. And how weird that is for me because it's through words and because my primary form of communication is not words. I was not a very verbal child. I'm not a very verbal adult. I'm a listener. I'm a feeler. And that's how I operate through the world, even though here I am talking again. And it's funny because this theme is coming up in a few of people I follow on Substack, there's one that just appeared today by

—I haven't read yet—talks about the pre-verbal or the ways we can communicate without words. And I wrote an essay last week In Defense of Nothing to Say, and it was inspired by my mom who's becoming less and less verbal as she ages. And part of that might be dementia, part of that might just be a contentment that she's experiencing and we instantly think, well, we need to connect with her more. We need to engage with her, bring her forward. And what I kind of realized in her quietness as she was taking in this whole family during a vacation, is that she's just becoming love. She's communicating beautifully. We just have to kind of slow it down, turn our shitter chatter down and all of a sudden there is connection there. There is vibration. So it's both again. It's the words that are happening that create these connections, but then it's also the limitations.Rebekah

And maybe thinking about words as doing different things. There's the words that are labeling and describing and organizing. And also there are the words that are like conduits to our bodies maybe or ways to connect, like tools or little prompts to try to move beyond language. I mean, if that's possible—language that helps us move beyond language, I don't know.

Kimberly

Yes, well that's probably what I'm experiencing with your writing because there is language that helps us move beyond language. Just the fact that you know we can read something and then close it and cry means that words took us to a place of wordlessness. So yeah maybe it's just a specific type of writing—poetry does this.

You actually—let's talk about love. You have another extraordinary essay called An Ordinary Unimaginable Love Story, where you challenge cultural assumptions about who is lovable and how. I want to know what did it mean for you to build a relationship from scratch and one that honored both your body and your full self.

Rebekah

Mm-hmm. That was the first essay I wrote for my book and maybe my favorite one to write. And it was such a delight to write that essay. And I think it was a delight to build a relationship that felt like I was setting the terms for the first time. know, it was starting from scratch, as you said.

I guess a little backstory would be, I mentioned that I grew up quite disembodied. And I think part of that resulted in a person who looked outward for what I thought love was supposed to look like and feel like and the forms it was supposed to take. And also there's, you know, there's this whole other set of fears and stories that come when you are visibly physically disabled teenager and what you imagine is available to you. I grew up in the age of rom-com, so I'm absorbing all of the narratives about what this is supposed to look like. It was very difficult to imagine myself into that. And so I ended up in a relationship with someone that was, it was not a very great fit. And part of it was that we were both just very young, but it felt to me like, this was my only shot. It was a fluke that this person wanted to be with me. And even if it wasn't the best setup, it was sort of like, Well, do you want to be alone forever? No? OK, this is what we're doing. So it was very like an intellectual decision to go forward with that relationship. And it was very much like this exercise in trying to create a relationship that looks like something. Because I didn't have any other barometer for knowing how to move forward.

The goal was just to create something that people could perceive as a great love story, I guess. I would not have had the language to describe it that way at the time. But in retrospect, I'm sort of, I can look back and see the ways that my body was trying to send me a lot of red flags that like, This is not the direction we want to go. And my head was like, This is the only direction we can go.

So all that to say, I think it really, I think a way to picture what that looked like really culminated in my wedding that I had when I was very young. was, you know, hitting all the marks of what this love is supposed to look like down to like the extremely poofy wedding dress that I had that was like the worst fit for a wheelchair. I was like running over it all day. Like what, why would we choose this? Oh cause I've seen it. Okay. yeah.

Or like the wedding pictures, like my wheelchair was taken out of all of the wedding photos. From the posed ones, Yes! I mean, and that was kind of a common thing for me at the time. I mean, like I was used to that. Oh Kimberly, I wish I could find this picture. One time I was a bridesmaid and the wedding photographer did not know what to do with my wheelchair, and so she just had me sit on the floor next to all the standing bridesmaids and my chair was just like taken out. Anyways, it's just this whole dance of like, we don't know how to include this. We don't know what the visual is supposed to look like for this wheelchair. So we'll just find tricky ways to get rid of it and have you propped up here or sitting in a different kind of chair. You know, it was this whole exercise in creating the image of a love story that looked like ones I had seen before. And that played out in every possible little way of that relationship. And really I got out of that relationship because my body protested very hard.

Kimberly

How did that happen?

Rebekah

Yes, I will tell you. I say this with so much pride in my body's care for me. Eventually, I mean, we had been married maybe four months when I couldn't eat anymore. I could hardly drink water. I was not sleeping at all. My heart was pounding all the time. I felt like I wasn't gonna survive and I couldn't explain it to anyone. I didn't know. I mean it wasn't like I literally thought that I was gonna be physically harmed. My body was just in distress and like throwing up every red flag, like the ship is going down, and I ended up moving back home, which we don't have to go into this whole story, but it was a bit of a miracle in itself.

My family was very, very, very, very anti-divorce. And they were a part of a church community that was adamant that they not let me move back home. And they did, they did let me move back home. And I immediately started sleeping again and felt a peace in my body. And all that to say, I mean, that was sort of the beginning for me of paying attention to like, what was actually happening in that relationship and recognizing things I had been ignoring for a really long time.

Kimberly

How did you know to listen to that as red flags coming from your body versus a lot of people would just go to a bunch of doctors, you know, they’d just be like, all right, I gotta fix this. Something's wrong with me.

Rebekah

Well, I think there was that. There was some of that. mean, it was a number of things too. I mean, it was like crying all the time. I just couldn't stop crying. And a lot of it was specifically related to the guy I was with, like I would just recoil when he touched me. Like a lot of it that seemed kind of directly related to that. And I should mention, like, I had my first panic attack of my life as we drove away from the wedding. Like, it was, yeah, I mean, was very, the pieces were all there. And I did, I mean, I was going to the doctor a lot during that time. So it wasn't like super, it wasn't so clear cut.

But, I think that I had lived so long succeeding at ignoring my body. There was so much that needed to be processed that was just bubbling up and bubbling up until it just couldn't be sustained anymore. And it was the first time in my life when I couldn't just conquer that through my will.

And so when it did start to billow out, it wasn't just—I feel like I'm like trying to condense like six lifetimes into this little, I don't want to talk about this the whole time ao I apologize if this is like confusing to follow—it wasn't just that I was processing that relationship. I was beginning to process like a whole lifetime of grief and fear and trauma.

It was almost like the relationship itself wasn't the thing. It was like the tipping point. And leaving that relationship wasn't even necessarily just because, everything else was fine, but I just was with the wrong person. It was like this whole life that just hadn't been, I hadn't been present for. And this was sort of the—

Kimberly

Yeah, that makes so much sense. That absolutely makes so much sense.

And it's important to recognize those pivotal moments in life and to not pinpoint them onto one thing, you know, and blame it on one thing because we are such multi-layered human beings and to just say that it was about your relationship doesn't honor everything that you had been and that you were trying to become and the unknown that you were stepping into.

Rebekah

Yeah. Yeah. I think that also there's another person that's very tied up into that story, right? I mean, that's something we think a lot as writers of personal life too, is like, I know my experience and I feel really careful about, I would feel incredibly resistant to the idea that we could just sort of blame a relationship and sometimes by extension, like a person for this going down. In some ways, I feel like that relationship was just a really sad casualty to a much bigger sadness of, you know, a much bigger set of losses and traumas to process. And he kind of got caught up in that without either of us really knowing that was was happening.

Kimberly

Collateral damage.

Rebekah

So, yeah, that's the word, I think.

When you think about the story of your own life, it is very easy to try to pin things into a linear, easy to track, one thing led to the other led to the other. But you're right, it's so much baggier and more billowy than that. It all starts at the beginning and in the middle and it goes sideways and backwards and all of it.

Kimberly

Yeah, and then you move forward into becoming a mother.

Rebekah

Yes, yes, your question was about starting a new love and I just went told the whole—

Kimberly

No, but it's all part of it. I was just thinking as you were talking, again, sort of this, this messaging from your body and these first signs of like that there's some someone there to listen to. But then I was thinking like, How did Otto—what was that part of your life like when he came in? I'm sure he's teaching you about embodiment in a whole new way?

Rebekah

Yes. I mean, wow, it's been a doozy in the best way. I'm trying to think if I should pause to say anything about Micah in between there. I I think what I would add, just since we have all the context now of the backstory, is that when I found Micah, who's my partner, we've been together for like 10, we've started dating 10 years ago, I guess.

So we've been in other's lives for a long time. There was something very exciting about getting to set the terms and recreate a love that honored both of our human experiences, our differences, our what we meant to each other, what we wanted to mean to each other, how we wanted to build this thing. So that felt wonderful and exhilarating.

And I found out I was pregnant and imagined myself as a mom, I kind of imagined it as an extension of that, like sort of this continuation of like, I'm gonna set the terms and I'm gonna create something from scratch that suits me and that excites me. And Otto is just this gloriously whole dynamic, vibrant reverberating self of his own. And I am like, from the first moment he was born, I have just been like holding on for dear life. Like, where are we? And what do do about this? What do I really think about this? And who am I really to this person? And how do I— a million new questions and have felt especially that first year, just so disoriented by this new being that I was inextricably and wonderfully and terrifyingly tethered to.

And there were lots of questions for me about motherhood and what it meant to be a mother and I didn't embody that role in the way that I had seen it. And I didn't think that would be hard because I already understood, you know, there's lots of ways to be a partner. There's lots of ways to be a mother. And somehow, like when I actually moved into that role, it was devastating to me to not embody it the way that I had seen it or even wanted to. I think it was the first time in my life that I deeply and genuinely grieved the limitations of my body in really specific ways. Everybody always told me before Otto was born that the way I moved through the world on wheels, like this motion would be comforting to him because that was the motion he was used to when he lived in my belly. People told me that with lot of confidence. It did not turn out to be true.

He wanted to be, he cried a lot as a baby. And the only motion that seemed to soothe him was Micah pacing and bouncing and pacing and bouncing around the house. And I couldn't recreate that motion. And it was devastating to me that I couldn't offer that to my son. And I would hear him crying and I would try everything to soothe him. And I couldn't do it. And I would have to hand them off to his dad, which is wonderful. What a beautiful thing for them to share. What a beautiful thing for Micah to be able to offer him. And also, I was devastated that it couldn't be me and that I couldn't do it.

Yes. So that was five years ago now. He's almost five. And we have moved through so many different phases together.

Our relationship, and my perception of our relationship maybe even, has shifted just as his needs have changed, you know, that window of when their mobility is limited is so small and our connection to one another has shifted as he's gotten older and very independent and mobile. One of the things I think I've seen over time that has paid off is not minimizing the grief of some of the ways that I've felt the limits of my body. I think that that grief is legitimate and worth letting it move through me.

And also I have seen the ways that leaning into my physicality, the limitations of my body and kind of bringing Otto into that world is also a gift that I have to offer him. And I see it really tangibly in the walks that we take to and from his school to my car. He started daycare when he was two, when I first started dropping him off or picking him up from daycare every day, I noticed very, very quickly that we moved through those spaces much, much more slowly than the other parents. That the other parents were like into the car, out of the parking lot, and we were still just like making our way down the sidewalk and stopping every other foot to look at something or.

Kimberly

Which is more like a child's pace.

Rebekah

Yes, and it's my pace. Yes. And so I think what I started to realize, at first, I really tried to match the other parents. It felt important to me in this sort of quest to assert myself as a legitimate mother and to be seen as a legitimate mother. And I started to realize, like, we get to do things in our own way, in our own pace, in our own rhythm, and that's better for both of us. And we don't have to match.

And I have slowly learned to lean into that and recognize that there is value in whatever unique shape that we are to each other. It's been a long time. It's taken me a long time to learn that. And it is much harder than I expected given that I've, I've literally defined ableism and could talk, do a whole hour on internalized ableism and why it's, like why these are not true stories. And yet in my own experience of it, was hard for me. It's been hard for me.

Kimberly

The title of your book is so perfect Sitting Pretty because it sort of encompasses all the things that you thought you should be in this world and all the the internalized ableism that you are experiencing in the world and this sort of here I am and I'm just going to fit myself into the world and it's like you're slowly peeling all of these back to Sitting Rebecca, sitting all of you, everything that you are, which is as I'm experiencing is full of—because you have that curious, insatiably curious mind—it's full of gold. And I feel like anyone, your readers, Otto, Micah, just gets to benefit from that because it makes us question how we've been conditioned too.

Rebekah

Thank you for that. Maybe that's my next book, Sitting Rebecca. Yeah, I do think that there has been an evolution in the stories that I am telling and what feels important to me about them. I wrote that book Sitting Pretty like five years ago. It came out five years ago now. And I do think that there are a different set of stories and maybe they, hopefully they still have humor in them, but I think that there is like a sobriety that has come with time and age. And we haven't even talked about Micah having cancer during Otto’s, like during pregnancy and the early days of motherhood. And so that was also a layer to just the complexity of life and how hard and magnificent it can be to live here and witness it.

Kimberly

Yeah, it's not static. It's one thing that we've, you I've experienced, I've experienced from the people in the unfixed community work. It's like, there's nothing static about being embodied and being true to that embodiment.

How do you feel about, so I know your storytelling right now is very personal and very rewarding for your readers and maybe still rewarding for you, but it sounds like there's some curiosity to maybe explore other things. You wrote, and I can't remember where you wrote this, but you said, “What creative whim could possibly feel worth sharing when the world is on fire”—because of everything we're going through right now, in this world and even within the disability community.

So what is helping you kind of hold a space for writing that feels personal while the world is on fire?

Rebekah

Mm-hmm. I think what has meant a lot to me is reading other people who are telling their own personal stories, us into their own little corners and seeing the value in that for me. I think we both mentioned

before we hit record of like a Substack of like reading Andrea Gibson's essays about sickness and they’re very ill and right up close next to that thin line of like passing on and witnessing that in real time has been a tremendous gift. And not only in its own right, but I think that feels really relevant for the world that we live in. Like looking closely at this feels urgent too.I think about the essay that you wrote about efficiency and caring for those cats, the stray cats. I still have very vivid images in my mind of the descriptions of the care and the messiness of that care that you offered. That feels relevant. That feels urgent to me right now. And so I think if I can believe that about the things that you and Andrea Gibson are writing, then I have to believe that for me. And I think that that goes back to that faith piece of it—that's like, I have to have this faith that what is alive in me, what is true in me is important, that bearing witness to that is important, that it matters.

So I think it's mostly being able to see that in others that makes me remember that and believe that. But it's hard. The world is overwhelming and scary and figuring out how to breathe in and out, let alone put a sentence together can be really hard. So I guess I also want to acknowledge that.

Kimberly

Mm-hmm. Yeah. You and I also referenced this before we—we talked about so much for like a half an hour, I should have pressed record—but we were talking about Substack, as you continue to grow on Substack, I think you'll start to see how those personal stories translate to deeply universal themes and also move people to places that they need to be moved to or they want to be moved to. And it comes through, you know, these connections that are just rich. And I don't think I've, I never thought that my memoir was something to share. Never, never, never, never, never. I was just like, family, here you go. You can understand what happened to me. I did not know that it would speak to people.

And how would I know, I guess, until I shared and then people pulled on those themes and the word unfixed became not so much, you know, just this personal experience of chronic illness, but that this world is unfixed and we can look at that through the lens of climate change. We can look at that through the lens of every uncertainty that we encounter. And it becomes so much more accessible when it's through story.

Rebekah

Yes, yes, I think so too. I think that we can—it's so funny to use words to connect in the wordless. I've never really thought of that framing of it. But I think it reminds me of when I was in graduate school and this was like, I don't know, 2016, 2017. So a different world in some ways and similar in some ways. But I remember when I was started out on writing creative nonfiction, a professor of mine was talking about the personal. And with personal writing and memoir, there has long, I mean, like since this genre has existed, there's been this criticism both internally and externally, like from people who create it and people who witness it as like self-indulgent, navel gazing, like, what are you doing?

Why is your story so important? Blah, blah, blah. And I remember my mentor, my beloved mentor in graduate school saying, like, If you can tell a story, if you can get so deep down, like the deeper down into the very specific heartbeat of a personal moment, that that will translate into something universal because that is the true seed, like there is something there. If you can find what that is and you can capture it and tell it that deeply true personal only, you-think-you're-the-only-one-in-the-world moment, that unlocks something much bigger, that that will inevitably feed into these big themes, these huge questions that we are grappling with as a species.

Most of the time, you know, I can tap into that and believe that. Sometimes it just, I am so stunned that I freeze, but I think of her often in giving me that nugget.

Kimberly

We're at an hour—and I wanna ask you, this is a horrible question!

Rebekah

I can’t wait!

Kimberly

But because we've been talking about this whole arc of the body of your work, I mean you even have a podcast now and it's not centralized on disability, it's you and your friend talking—so I wanna know as this journey of your life continues, going deep, deep, deep down into the seed that will speak universally to the world. What is that for you now? Or what is that evolving into? What does that look like?

Rebekah

That is a terrible question, Kimberly! No, I mean, it's a great question because it's like, I think that that is an important like reflection point. I mean, one of the first things that comes to my mind is the both/and of being human. I mean, it's funny that we started this conversation with this like, Am I a writer or an advocate? You know, these binaries and I think the world we live in, and maybe this has been the case forever and ever in different ways, but I think that our brain seems so prone to binaries and wanting something to be this or that, tragic or triumphant. That's why I love the word unfixed so much. I mean, I think that there's so much that can sprawl underneath that word. It's expansive. It invites questions.

So I think for me, I think so much about the value of practicing the both/and and cracking the doors open for more and more of that in our experience of the world. I mean, especially right now, it can be at a fever pitch when we feel like we must choose one or the other and it is black or it is white and it is this or it is that and it can only be this or it can only be that.

And that's hardly ever true. I think so much of the time it's this layer and this layer and this layer and I and I want to be able to name every one and I want to be able to hold on to two or three or four even when they contradict I want to look at all of it. The Substack that I started last year is called This Too, and I think that's part of it as well. It's this and this and this and this, too.

So I think that's part of what has become a defining thread/arc through the things that I ponder and write about. I think that there are other themes emerging over time. You named curiosity in the beginning and maybe a part of This, Too is just like almost inconvenient, exhausting curiosity of just wanting to see more and understand more and pull back that layer too. So I think those are some of the things that I see as always running through what I'm doing. And maybe it's because to me, writing is the space of discovery and writing is the tool for understanding and making sense. so that shows up in my writing a lot.

Kimberly

Yeah, absolutely. It's even, like we've talked about as a thread through here, it's both—it's even the words that are allowing for the wordlessness.

Rebekah

I love that, this is something I'm taking with me. The words that take us to the wordless, I love that.

Kimberly

And that it's just such a perfect way to allow this both/and experience too, because some of us are like, well, I'm, I'm nonverbal or I'm an introvert or I'm gonna, it's like, it's all, it's all there.

Rebekah

Yeah. In context, in conversation, evolving, pivoting, revising, backtracking, leaping forward, jerking this way and that. I mean, yes. And being able to have the capacity to bear witness to all of that and not getting stuck in a pattern of building stories where I'm looking for the pieces to build the story I already have in mind. But being able to bear witness to the organic and great unfurling of whatever is there.

Kimberly

Yeah, and it is great. You are great. This is just, thank you so much. Boy, I just wish I could reach through this screen right now and give you a big hug.

Rebekah

I feel it, I feel it and it's mutual. I feel like you're offering your people such a gift in these conversations. The generosity of your questions and the insatiable and gorgeous curiosity that you have and your desire to see people deeply is so apparent.

Kimberly

Thank you for seeing me. That's very true. If I know one thing to be true, that's true.

Rebekah

It's true.

Kimberly and Rebekah

MWAH!

Oh, my dear friend. I'm returning to this conversation with a fresh gratitude for you. Your generous curiosity, your abundant presence, your rare ability to really witness the person you're sitting with. You are a wonder! And you are clearly creating such a thoughtful community here. I am so hungry for this kind of slow and intentional reflection together. THANK YOU for inviting me into this space with you💛✨

Well, this was wonderful. I love these interviews. And I love when they introduce me to somebody new, somebody whose work, whose writing I can’t wait to check out.

Let me tell you when I first really teared up during this conversation. When you, Rebekah, talked about how proud you were of your body’s decision to send up red flags and tell you you needed to make a change. And a whole lot of welling up happened after that.

And I wholeheartedly agree. Kimberly’s gift of seeing people is wondrous.

Thank you, Rebekah. Thank you, Kimberly.