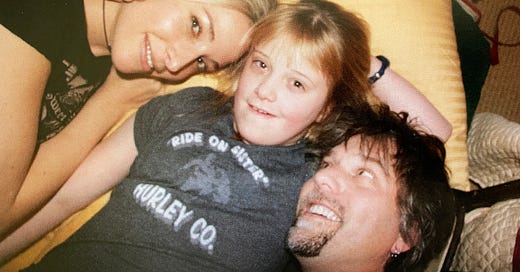

Near the end of my first year at NCNM (renamed NUNM during the 2 year hiatus), Dave and I meet on a commercial photoshoot. Straddling school with occasional modeling jobs somewhat pacifies my more creative inclinations. On this gig, I’m booked as a ”yogini” for a Nike mother’s day video. Dave is a creative director on a neighboring set. …

© 2025 Kimberly Warner

Substack is the home for great culture