April 3, 1993

Dear Charlie,

This morning, April 3rd at 5:43, on Highway 43, dad’s car collided with a Mac truck. He’s dead.

I feel numb. I feel nothing.

Earlier today mom, Eric and I were at the Cancun airport. She led us outside to a pink, flowering bush and knelt down in the dusty earth. She asked us to join her.

I was numb. I felt nothing.

If she had asked me to swallow an iguana whole, I would’ve said yes. Just tell me what to do.

While happy flowers mocked our reality, mom said that dad wants us to live our lives fully.

I don’t know what this means.

I’m in mom and dad’s bed now. Dad’s side still smells like him. We’ve traveled over 6000 miles in less than 24 hours. When we left home, I was thinking about blue Gulf of Mexico waters and the new pimple on my chin. Now, here I am. Numb. Through the oatmeal after-effects of a sleeping pill I try to sort through this morning’s events. But I can’t think of anything except dad’s request — or was it mom’s?

“Dad wants us to live our lives fully.”

There was an anesthesiologist from Appleton Medical Center driving behind dad. He recognized dad’s car and vanity plate. He said moments before the collision, dad reached his hand through the sun roof and waved to the rising sun. Was he waving hello?

Or was he waving goodbye?

Does his spirit exit stubbornly

clinging to ribcage and bone

or was he squeezed out like toothpaste

from a phantom umbilicus?

Maybe some rise easily, like the yeasty force of leavened bread,

warmed to meet a new infinite ceiling.

Maybe others catch on spinning fans and ride out eternity

on a dizzy blade.

Or is it simpler than all of this —

after car crushes

heart ceases,

breath escapes,

we mistake a vacant body and

it’s yawning void

for a soul.

We name it, we animate it, we call for it

but it’s only

so our own void has a place to go.

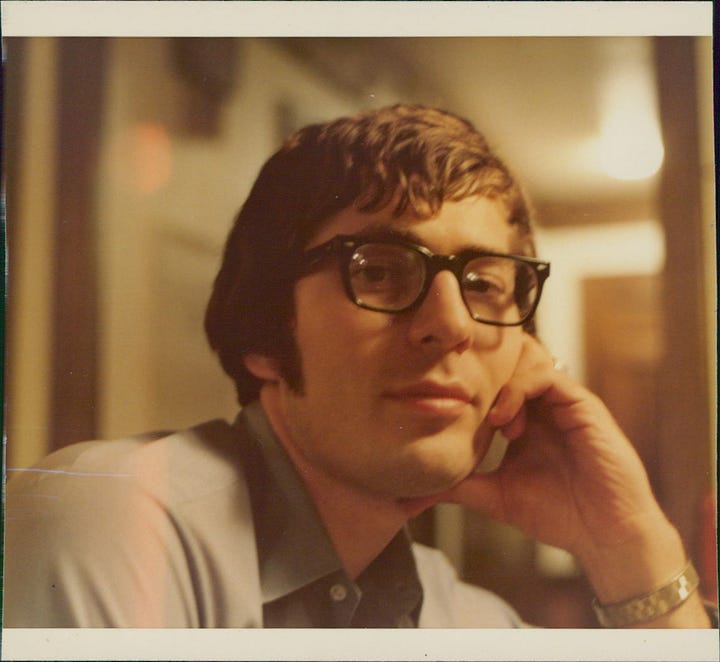

The strange and complicated relationship mom and dad shared is irreparably broken when he doesn’t return from a hospital staff party. He and his surgical partners had dressed as famous musicians and sang farewell tunes to a retiring nurse. Luis Suarez was Julio Eglesias. Trevor Rattray was Harry Belafonte. Dad, already halfway there with his pony tail dressed up as Willie Nelson. Twelve hours earlier he had bypassed a cheese-encrusted artery and saved a life. Twelve hours later he drove head on into a truck.

He dies on Highway 43, right before the two-lane road splits into four. The insignificant little town of Fredonia cradles his crushed ribs that morning as his spirit unfurls its tireless wings. Or maybe they were tired. I don’t know. Highway 43. At 5:43. On April 3. 4/3. He was also born in 1943. This number will haunt, comfort and deceive me for the rest of my life.

There is a neatly folded napkin. A Wisconsin area code phone number is scribbled in pen. I can’t read anything in the flight attendant’s face as she hands it to mom. It’s as if she’s handing mom a bag of peanuts. So I look at mom’s expression. Does the furrow in her brow express concern or is she just tired from her 2 am alarm? Who is trying to contact us while at cruising altitude? The long, early-bird drive from our sleepy northern lake town to the Milwaukee airport is always grueling, but the promise of a Mexico sunset less than twelve hours later keeps our spirits lifted. I convince myself that mom’s furrow is fatigue and that everyone receives phone numbers on napkins while flying the friendly skies.

After all, it is my senior year spring break. I want smooth sailing in those final months of high-school, and resent anything that interrupts my “seize the day attitude.” I frequently quote my favorite film, Dead Poet’s Society, especially the part about “sucking the marrow out of life,” and feel like a failure when I can’t seem to find that damn marrow. But when I do, as fleeting as it may be, my idealistic nature puffs up with validation. See, I CAN control my reality.

Eric left the nest two years earlier. He occasionally sends me cool, big-brother mixes on cassettes with Colorado bands like The Samples and Big Head Todd and the Monsters. In my mind, he bought an automatic ticket to cool-dom when he moved to Colorado, started wearing Patagonia and carrying a Nalgene water bottle everywhere he went. I wear the Dr. Seuss and PowerBar tees he leaves behind but swim awkwardly his 6’6” frame threads.

The plan is for Eric to meet us in the Cancun airport. As my butt grows weary on the airplane, cryptic phone number long forgotten, I imagine the big bear hug I’ll receive from Eric as he emerges from airport customs. Dad will match the embrace (and then some) with his famous “four-seconds-too-long” hug.

I search my memory and those hugs are not there. I hate that I can clearly see the Duty Free shops and over-tanned tourists. I hate how vividly I hear the thunder of overstuffed luggage rolling by. And I hate it more for not drowning out the sound of Eric screaming “Nooooooooooooooooo!!!!” as he falls to his knees.

Mom and I didn’t get on the airplane in Milwaukee with dad. Flight number 134 departed at 6:00am, and when dad didn’t return home from the hospital party by 2:30am, mom was pissed. She tossed out a few short, pinching remarks about dad never keeping his commitments—I’m done forgiving him!—and then threw our packed bags in the car.

“He’ll have to drive himself to the airport,” she said and left his flight information on the bathroom counter. The ice in her words cut through the fog of that early spring morning. I stopped breathing deeply somewhere within these moments and am not sure if I ever completely retrieved those O2’s. Sucking in too fully might’ve surfaced a sea of intuition in my gut that knew something was already terribly wrong as we set foot on that plane.

I wish I had felt something, noticed a bird soaring outside our gate’s window, saw a child and father embrace near the Apple Vacations ticketing counter. Something. Something that indicated that at 5:43am dad’s soul broke free from the jaws of life, just a half hour behind us on Highway 43, racing to make the flight. Instead, I probably sat with my carry-on between my feet, obsessing about a zit on my chin and what flavor muffin I would buy for the long flight. Mom, consumed with rage, marched to a payphone and canceled reservations at the Wagon Wheel for their upcoming couple’s retreat thinking, We are shams. How dare we teach Conscious Loving workshops when ours is so broken. She digs through her over-sized purse for the conference center’s phone number. If she felt vulnerable and shaken to the core in that moment, it was imperceptible. Her symmetrical, elegant bone structure never gives way to the storm of emotion underneath.

That morning was the first time mom said “No” to a twenty-five year dynamic with dad, one of broken promises and weary forgiveness. That morning she chose to not wait for him. That morning, she drove right through the little town of Fredonia without him.

Mom likes wordplay. She breaks apart the town name Fredonia and says it means Fré Donné — free the woman. Eric and I think this is a powerful piece of the story, perhaps even a message from dad beyond the grave. Was it his last wish for her? To free her from the endless cycles of betrayal and reconciliation? This little town name holds the secret to dad’s salvation and consoles his family’s desperate need to find meaning.

I am looking into the etymology now and I can’t find anything that says that Fré means “free”. Instead, I read that it originates from Old French freid from Latin frigidus. It doesn’t mean “free.” It means “cold.” Cold woman?

Cold Woman or Free the Woman. I laugh out loud. Which narrative would you choose?

That morning was the first time mom said “No” to a twenty-five year dynamic with dad, one of broken promises and weary forgiveness. That morning she chose to not wait for him. That morning, she drove right through the little town of Fredonia without him.

I want to paint a picture of what I think happened to dad that foggy April morning. I want to trace his thoughts. Did he feel abandoned by us when he returned home from the party? Did he feel guilty? Was he sleepy from a previous day of life saving or was he drunk from a night of Willie and wine? Was he happy?

When he pulled into the garage, he would have already known that mom and I had left. I know he was in a hurry because we saw, twenty-hours later, his clothes thrown out on the bed in a frenzy to pack for a week in Mexico. I bet he packed in less than 5 minutes, remembering all the necessities of wallet, pager, and that bristle brush he loved for a good head scratching. I know he saw my mom’s note in all caps—MEET US IN MEXICO. I’M PISSED. Underline, underline, underline. I know this because the county police found it in the passenger seat of his totaled car and had to fleetingly investigate a possible suicide.

So in less than five minutes, he grabbed the note, traded briefcase for luggage, maybe chugged a glass of water in the kitchen. That’s it. So why, then, WHY, did he take time to scotch tape a cartoon from yesterday’s New York Times onto the bathroom mirror? We found it on the bottom left corner, just above his bar of sandalwood soap. A line drawing of a bearded man climbs the face of a steep mountain looking weary. The caption below him reads: Life is but a game. Too bad the batteries aren’t included.

Was he waving hello or goodbye to the rising sun?

I wonder if that cocktail napkin and its scribbled phone number have completely decayed in some Mexican landfill by now? Did the sweat of mom’s hand gripping its folded edges speed up the decay? And if it never made it to the dump truck, but instead drifts on holiday breezes, touching down temporarily in gutters, sidewalks and little boy’s hands, does the coroner in Fredonia ever get international prank phone calls?

I wish we had been the recipient of a bad prank. I stand at mom’s side after we pass through customs. It doesn’t take her long to get through to the states, the operator unknowingly connecting mom to her widowed destiny. Mom looks at me sideways; I’m sure she’s irritated that I’m not near our luggage. Let the Texans have my flip-flops, my new spring-break sundress. I need to be near mom as she makes first contact with the human behind the phone number, not to comfort her, but to selfishly feel some sense of control. Something isn’t right. I claim the concrete floor beneath my feet and don’t budge until the operator connects mom to — — -

Turns out that concrete under my feet is quick sand. My head spins. Am I about to pass out? My brain pounds with vacant incomprehension as mom’s lipstick stained mouth forms the words,

“Dad’s dead.”

The only thing that separates this moment from a complete black-out is a thin membrane of awareness. The roar of luggage rolling on concrete. The deafening hum of voices going this way, then that way. Instead of my body going limp and surrendering to the fat, grandmotherly arms of a passing tourist, I freeze. This is what trauma therapists speak of when they refer to “fight, flight, or freeze.” I am clearly of the popsicle variety.

Cold transforms to numbness. Numbness removes sensory perception from reality. And somewhere in this slow, slipping away from my environment, denial makes itself at home. For the next twelve hours I convince myself that mom is nuts, Eric is overly dramatic, and dad is safe at home smoking a pipe and reading an Ann Rice novel. I dissociate. Little gasps of air seep into my rib cage. If I breathe too deeply, everything will crumble.

I sit next to Eric on the flight back to the midwest and listen to his new mix for me. Some marijuana induced moment back at CU Boulder probably inspired his hand written title, but I smile now at its poignancy. “Time Stood Still.” I listen over and over again to the Bob Marley song, “High Tide or Low,” drowning out the angst that keeps trying to surface. Later, I will listen to this song, forever the soundtrack to the day dad died, and try to decode it. Another message from beyond the grave. Another attempt at making meaning from the ambivalence of life.

We land in Chicago and fat snowflakes fall from the sky. I am comforted by the snow, muting and then extinguishing the queasiness in my gut. We have a four hour drive ahead. Mom slows the car as we pass through the sleepy, snow-blanketed town of Fredonia. A kind flight attendant had slipped mom some sleeping pills on our flight back to Chicago and I can now feel the drug push into me like a heavy fog as I sit in the back seat. Distant farmhouses glow as winter asserts her strength over spring. It was just an ordinary day for the locals. Tired wives bought pastries at the local bakery that morning and children hid in hay lofts until the school bus arrived. That evening, not a soul is out. We pull to the side of the road where dad’s car had skidded into oblivion less than 24 hrs earlier. The snow already covers his tracks.

I notice the ground is slippery as I step out of the car. One misstep and I, too, will disappear into a timeless portal. When someone dies, does a thin veil open up between dimensions so souls can slip seamlessly through? How long does it stay open?

Mom suggests that we hold hands and scream. So we do. We scream so loud that I am sure lights begin to flicker on in neighboring houses. And for the first time in my self-consumed, self-conscious adolescent world, I don’t care. I am desperate for something real in that moment, a lone wolf calling to her pack. Snowflakes fall on my face as I looked toward the sky for dad’s response.

Nothing.

I notice the ground is slippery as I step out of the car. One misstep and I, too, will disappear into a timeless portal.

I put my mask back on. I crawl into the back seat of the car and resume my irritable and delusional state. I visualize the garage door opening at home, dad’s license plate “YANG” mocking us as we pull aside it. The more I burn this vision into my brain, the louder mom and Eric’s cries become. I want out of the car. I hate them for being loud and emotional. There is no room for me. I don’t know how I need to respond but I don’t want to do it their way. I become smaller and smaller in the back seat and eventually slip out from under my seatbelt, out the crack in the window, and into the arms of dad.

That night, after pulling into the empty garage I collapse in the meditation room with my journal and close the door. I look at my hands and try to see his in mine. Magical thinking consumes me. I make a pact with him that night that his hands can work through mine. I will follow in his path and take it where his abbreviated life couldn’t.

I had to take this one in in stages. Bits and pieces of this story I knew, but the details of those days...they broke my heart all over again. I wish I could have curled up next to you in the backseat for that long drive home. Kim, the work you’ve done to sift and sort your feelings and the details of those days lend a depth to your writing that I can’t really describe. I can picture it all...like reading your words walked me right through the house alongside you on your return and the grief made my stomach turn. All I keep thinking is, “where was I in those days?” I’d give so much to go back and be with you. I wish we could have carried this together. Thanks for letting me in today. I love you...and your sweet, dad.

such powerful, heartbreaking writing. Thank you for allowing us to reside in this fragile moment with you so fully.